Subgroups

On the author’s AMD Radeon 5600M GPU, avoiding shared memory bank conflicts is a major performance improvement. But not to the point where using shared memory ends up becoming an unambiguous step up in performance from the previous simulation implementation:

run_simulation/workgroup8x8/domain2048x1024/total512/image32/compute

time: [119.78 ms 120.16 ms 120.56 ms]

thrpt: [8.9060 Gelem/s 8.9356 Gelem/s 8.9641 Gelem/s]

change:

time: [-7.0218% -5.5135% -4.0137%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

thrpt: [+4.1815% +5.8352% +7.5521%]

Performance has improved.

run_simulation/workgroup16x8/domain2048x1024/total512/image32/compute

time: [101.57 ms 101.85 ms 102.21 ms]

thrpt: [10.505 Gelem/s 10.542 Gelem/s 10.571 Gelem/s]

change:

time: [-1.6314% -0.1677% +1.4719%] (p = 0.85 > 0.05)

thrpt: [-1.4505% +0.1680% +1.6584%]

No change in performance detected.

run_simulation/workgroup16x16/domain2048x1024/total512/image32/compute

time: [100.44 ms 100.61 ms 100.82 ms]

thrpt: [10.650 Gelem/s 10.672 Gelem/s 10.690 Gelem/s]

change:

time: [-10.130% -8.5750% -7.1731%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

thrpt: [+7.7274% +9.3793% +11.271%]

Performance has improved.

run_simulation/workgroup32x16/domain2048x1024/total512/image32/compute

time: [96.656 ms 97.088 ms 97.459 ms]

thrpt: [11.017 Gelem/s 11.059 Gelem/s 11.109 Gelem/s]

change:

time: [+3.3377% +4.4153% +5.6007%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

thrpt: [-5.3036% -4.2286% -3.2299%]

Performance has regressed.

run_simulation/workgroup32x32/domain2048x1024/total512/image32/compute

time: [112.13 ms 112.37 ms 112.62 ms]

thrpt: [9.5339 Gelem/s 9.5555 Gelem/s 9.5757 Gelem/s]

change:

time: [+13.281% +15.723% +18.845%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

thrpt: [-15.857% -13.587% -11.724%]

Performance has regressed.

It looks like for this particular GPU at least, either of the following is true:

- The GPU’s cache handled our initial data access pattern very well, and thus manually managed shared memory is not a major improvement. And if it’s not an improvement, it can easily end up hurting due to the extra hardware instructions, barriers, etc.

- We are still hitting some kind of hardware bottleneck related to our use of shared memory, that we could perhaps alleviate through further program optimization.

Unfortunately, to figure out what’s going on and get further optimization ideas if the second hypothesis is true, we need to use vendor profiling tools, and we will not be able to do so until a later chapter of this course. Therefore, it looks like we will be stuck with these somewhat disappointing shared memory performance for now.

What we can do, however, is experiment with a different Vulkan mechanism for exchanging data between work items, called subgroup operations. These operations are available on most (but not all) Vulkan-supported GPUs, and their implementation typically bypasses the cache entirely which allows them to perform faster than shared memory for some applications.

From architecture to API

For a long time, GPU APIs have focused on providing developers with the illusion that GPU programs execute over a large flat array of independent processing units, each having equal capabilities and an equal ability to communicate with other units.

However, this symmetric multiprocessing model is quite far from the reality of modern GPU hardware, which is implemented using a hierarchy of parallel execution and synchronization features. Indeed, since about 2010, GPU microarchitectures have standardized on many common decisions, and if you take a tour of any modern GPU you are likely to find…

- A variable amount of compute units1 (from a couple to hundreds). Much like CPU cores, GPU compute units are mostly independent from each other, but do share some common resources like VRAM, last-level caches, and graphics-specific ASICs. These shared resources must be handled with care as they can easily become a performance bottleneck.

- Within each compute unit, there is a set of SIMD units2 that share a fast cache. Each SIMD unit has limited superscalar execution capabilities, and most importantly can manage several concurrent instruction streams. The latter are used to improve SIMD ALU utilization in the face of high-latency operations like memory accesses: instead of waiting for the slow instruction from the current stream to complete, the SIMD unit switches to another instruction stream.3

- Within each concurrent SIMD instruction stream, we find instructions that, like all things SIMD, are designed to perform the same hardware operation over a certain amount of data points and to efficiently access memory in aligned and contiguous blocks. However GPU SIMD units have several features4 that make it easy to translate any combination of N parallel tasks into a sequence of SIMD instructions of width N, even when their behavior is far from regular SIMD logic, but at the expense of a performance degradation in such cases.

A naive flat parallelism model can be mapped onto such a hardware architecture by mapping each user-specified work-item to one SIMD lane within a SIMD unit and distributing the resulting SIMD instruction streams over the various compute units of the GPU. But by leveraging the specific features of each layer of this hierarchy, better GPU code performance can be achieved.

Sometimes this microarchitectural knowledge can be leveraged within the basic model given some knowledge/assumptions about how GPU drivers will map GPU API work to hardware. For example, seasoned GPU programmers know that work-items on a horizontal line (same Y and Z coordinates, consecutive X coordinates) are likely to be processed by the same SIMD unit, and should therefore be careful with divergent control flow and strive to access contiguous memory locations.

But there are microarchitectural GPU features that can only be leveraged if they are explicitly exposed in the API. For example, GPU compute shaders expose workgroups because these let programmers leverage some hardware features of GPU compute units:

- Hardware imposes API limits on how big workgroups can be and how much shared memory they can allocate, in order to ensures that a workgroup’s register and shared memory state can stay resident inside of a single GPU compute unit’s internal memory resources.

- Thanks to these restrictions, shared memory can be allocated out of the shared cache of the compute unit that all work-items in the workgroup have quick access to. And workgroup barriers can be efficiently implemented because 1/all associated communication stays local to a compute unit and 2/workgroup state is small enough to stay resident in a compute unit’s local memory resources while the barrier is being processed.

Subgroup operations are a much more recent addition to portable GPU APIs5 which aims to pick up where workgroups left off and expose capabilities of GPU SIMD units that can only be leveraged through explicit shader code changes. To give some examples of what subgroups can do, they expose the ability of many GPU SIMD units to…

- Tell if predication is currently being used, in order to let the GPU code take a fast path when operating in a pure SIMD execution regime.

- Perform an arithmetic reduction operation (sum, product, and/or/xor…) over the data points held by a SIMD vector. This is an important optimization when performing large-scale reductions, like computing the sum of all elements from an array, as it reduces the need for more expensive synchronization mechanisms like atomic operations.

- Efficiently transmit data between work-items that are processed by the same SIMD vector through shuffle operations. This is the operation that is most readily applicable to our diffusion gradient computation, and thus the one that we are agoing to explore in this chapter.

But of course, since this is GPU programming, everything cannot be so nice and easy…

Issues & workarounds

Hardware/driver support

Subgroups did not make the cut for the Vulkan 1.0 release. Instead, they were gradually added as optional extensions to Vulkan 1.0, then later merged into Vulkan 1.1 core in a slightly different form. This raises the question: should Vulkan code interested in subgroups solely focus on the Vulkan 1.1 version of the feature, or also support the original Vulkan 1.0 extensions?

To answer this sort of questions, we can use the https://vulkan.gpuinfo.org database, where GPU vendors and individuals regularly upload the Vulkan support status of a particular (hardware, driver) combination. The data has various known issues, for example it does not reflect device market share (all devices have equal weight), and the web UI groups devices by driver-reported name (which varies across OSes and driver versions). But it is good enough to get a rough idea of how widely supported/exotic a particular Vulkan version/extension/optional feature is.

If we ignore reports older than 2 years (which reduces the device name change issue), we reach the conclusion that of 3171 reported device names, only 57 (1.8%) do not support Vulkan 1.1 as of their latest driver version. From this, we can conclude that Vulkan 1.0 extensions are probably not worth supporting, and we should focus on the subgroup support that was added to Vulkan 1.1 only.

That is not the end of it, however, because Vulkan 1.1 only mandates very minimal subgroup support out of Vulkan implementations, which is insufficient for our needs:

- Subgroups only need to be supported in of compute shaders. That’s good enough for us.

- Subgroups of size 1 are allowed, as a way to support hardware without driver-exposed SIMD instructions. But those are useless for our data exchange purposes, so we will not be able to use subgroup shuffle operations on such implementations.

- The only nontrivial subgroup operation that Vulkan 1.1 mandates support for is the election of a “leader” work-item. This is not enough for our purposes, we need shuffle operations too.

Therefore, before we can use subgroups, we should probe the following physical device properties:

- Vulkan 1.1 should be supported, as we will use Vulkan 1.1 subgroup operations.

- Relative6 shuffle operations should be supported, enabling fast data exchanges.

- Subgroups should have ≥ 3 elements (minimum for left/right neighbor exchanges7).

Finally, there is one last thing to take care of when it comes to hardware/driver specifics. On many GPUs, subgroup size is not a fixed hardware-imposed parameter as Vulkan 1.1 device properties would have you believe. It is rather a user-tunable parameter that can be configured at various power-of-two sizes between two bounds. For example, AMD GPUs support subgroup sizes of 32 and 64, while Apple Mx GPUs support subgroup sizes of 4, 8, 16 and 32.

Being able to adjust the subgroup size like this is useful because there is an underlying performance tradeoff. Roughly speaking…

- Larger subgroups tend to perform better in ideal conditions (homogeneous conditional logic, aligned and contiguous memory accesses, few barriers, abundant concurrency). But smaller subgroups tend to be more resilient to less ideal conditions.

- On hardware where large subgroups are implemented through multi-cycle execution over narrower SIMD ALUs, like current AMD GPUs, shuffle operations may perform better at smaller subgroup sizes that match the true hardware SIMD unit width.

Subgroup size control was historically exposed via the

VK_EXT_subgroup_size_control extension to Vulkan 1.1, which was integrated

into Vulkan 1.3 core as an optional feature. But a quick GPUinfo query suggests

that at the time of writing, there are many more devices/drivers that support

the extension than devices/drivers that support Vulkan 1.3 core. Therefore, as

of 2025, it is a good idea to support both ways of setting the subgroup size.

Absence of this functionality is not a dealbreaker, but when it is there, it is good practice to benchmark at all available subgroup sizes in order to see which one works best.

Undefined 2D layout

We have been using 2D workgroups with a square-ish aspect ratio so far because they map well into our 2D simulation domain and guarantee some degree of hardware cache locality.

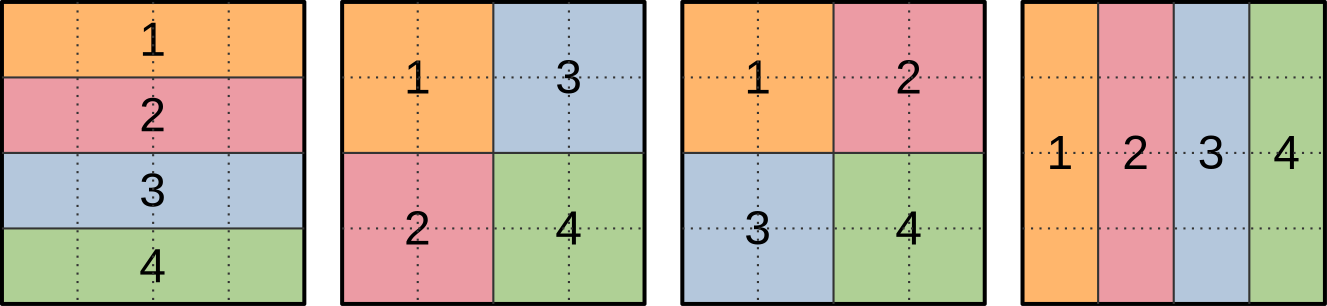

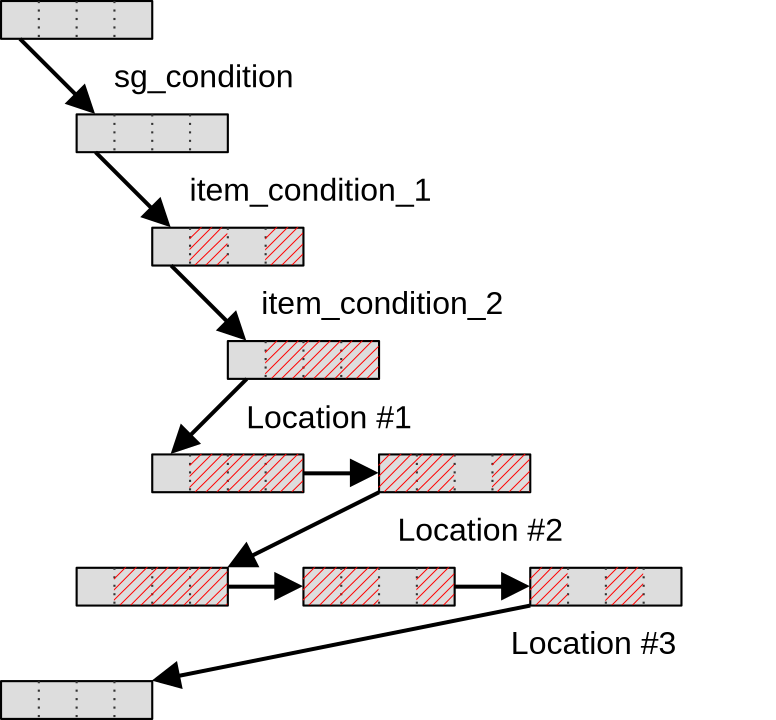

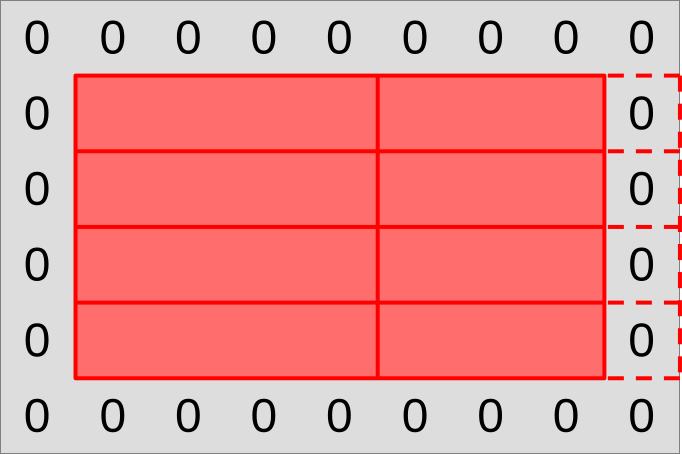

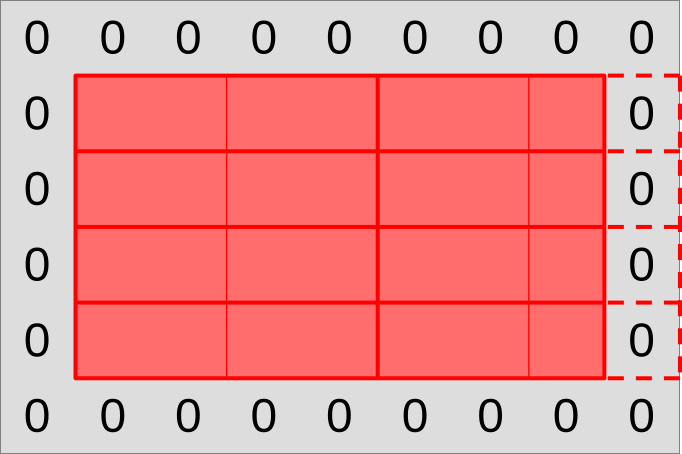

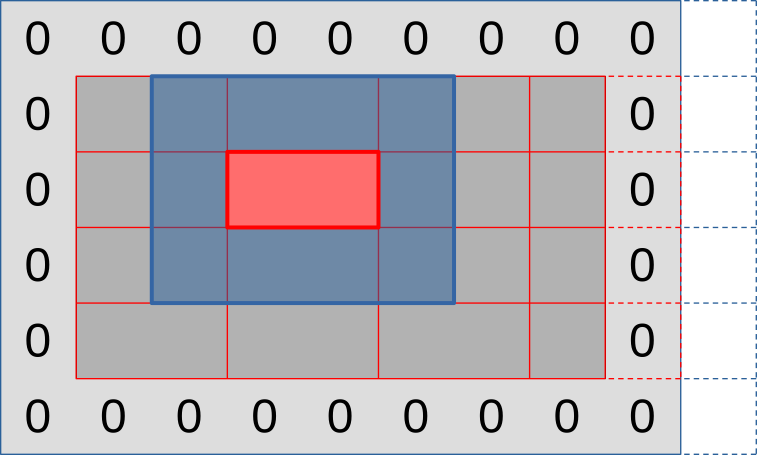

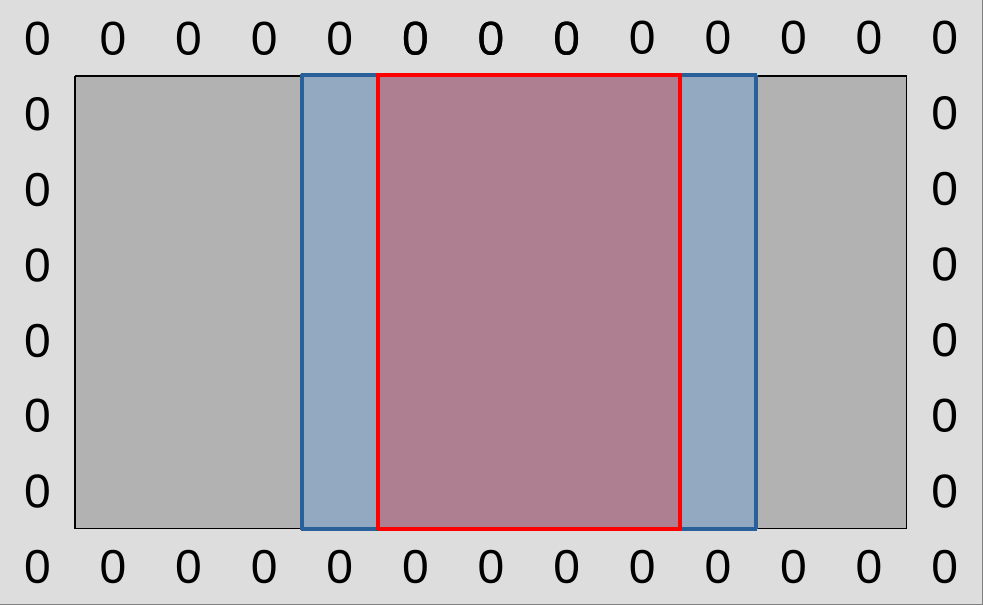

However, there is a problem with such workgroups when subgroups get involved, which is that Vulkan does not specify how 2D workgroups will be decomposed into 1D subgroups. In other words, all of the ways of decomposing a 4x4 workgroup into 4-element subgroups that are illustrated below are valid in the eyes of the Vulkan 1.1 specification:

This would not be an issue if we were using subgroup operations for data reduction, where the precise order in which input data points are aggregated into a final result generally does not matter. But it is an issue for our intended use of subgroup shuffles, which is to exchange input concentration data with neighboring work-items.

Indeed, if we don’t know the spatial layout of subgroups, then we cannot know ahead of time whether, say, the previous work-item in the subgroup lies at our left, on top, or someplace else in the simulation domain that may not be a nearest neighbor at all.

We could address this by probing the subgroup layout at runtime. But given that we are effectively trying to optimize the overhead of a pair of memory loads, the computational overhead of such a runtime layout check is quite unlikely to be acceptable.

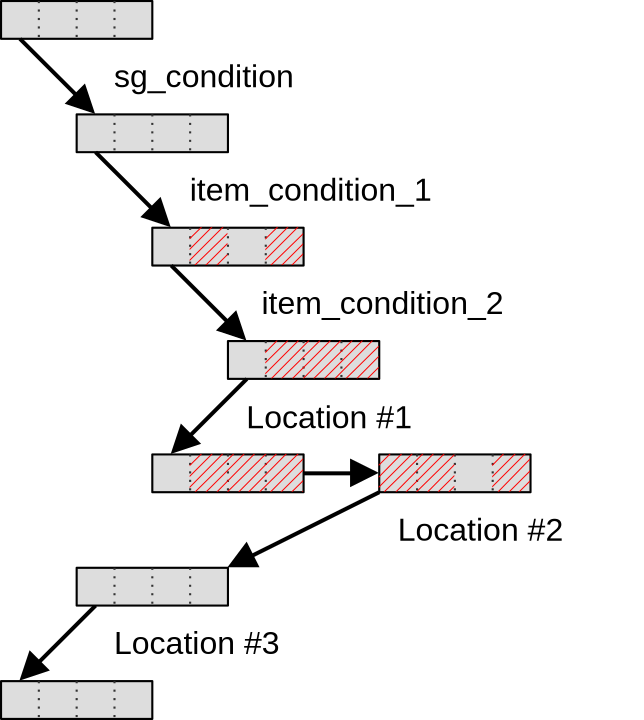

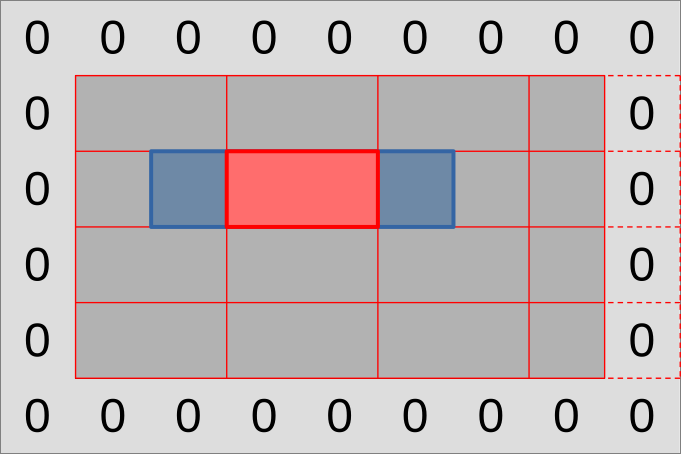

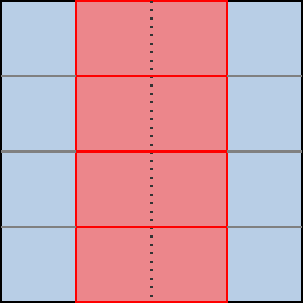

We will therefore go for the less elegant alternative of exclusively using one-dimensional workgroups that lie over a horizontal line, as there is only one logical decomposition of these into subgroups…

…and thus we know that when performing relative subgroup shuffles, the previous work-item (if any) will be our left neighbor, and the next work-item (if any) will be our right neighbor.

Speaking of which, there is another matter that we need to take care of before we start using relative subgroup shuffles. Namely figuring out a sensible way to handle the first work-item in a subgroup (which has no left neighbor within the subgroup) and the last work-item in a subgroup (which has no right neighbor within the subgroup).

Undefined shuffle outputs

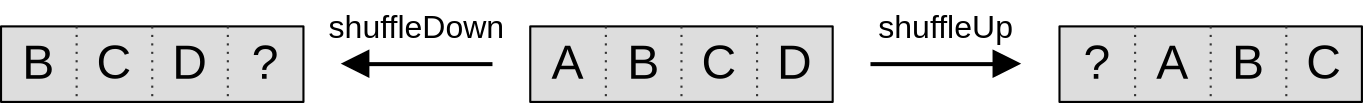

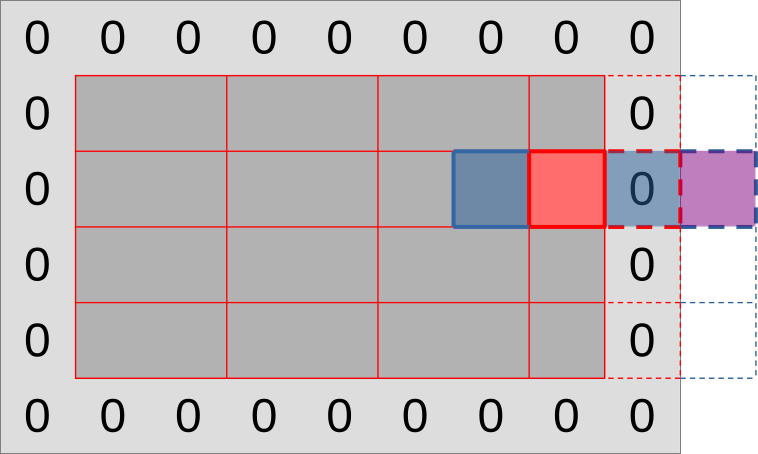

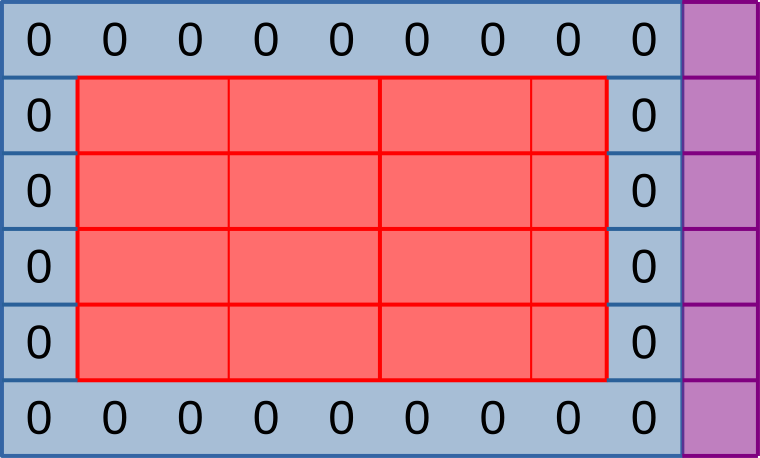

As mentioned before, our end goal here is to use relative subgroup shuffles operations. These effectively shift data forward or backward within the subgroup by N places, as illustrated below…

…but as the ? character on the illustration illustrates, there is a problem at the edges of the subgroup, where we are effectively pulling data out of non-existent subgroup work-items before the first one and after the last one.

The Vulkan specification declares that these data values are undefined, and we certainly do not want to use them in our computation. Instead, we basically have two sane options:

- We use subgroups in the standard way by making each element of the subgroup produce one output data point, but the first and last work-item in the subgroup do not follow the same logic as other work-items and pull their left/right input value from memory.

- As we did with work-groups back in the shared memory chapter, we make subgroups process overlapping regions of the simulation domain, such that the first/last work-item of each subgroup only participates in input data loading and exits early after the shuffles instead of participating in the rest of the computation.

The first option may sound seducive, as it allows all work-items within the subgroups to participate in the final simulation computation. But it does not actually work well on GPU hardware, especially when applied within a single subgroup, because subgroups are implemented using SIMD. Which means that if the work-items at the edge of a subgroup do something slow, other work-items in the subgroup will end up waiting for them and become equally slow as a result.

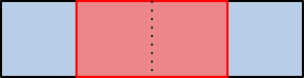

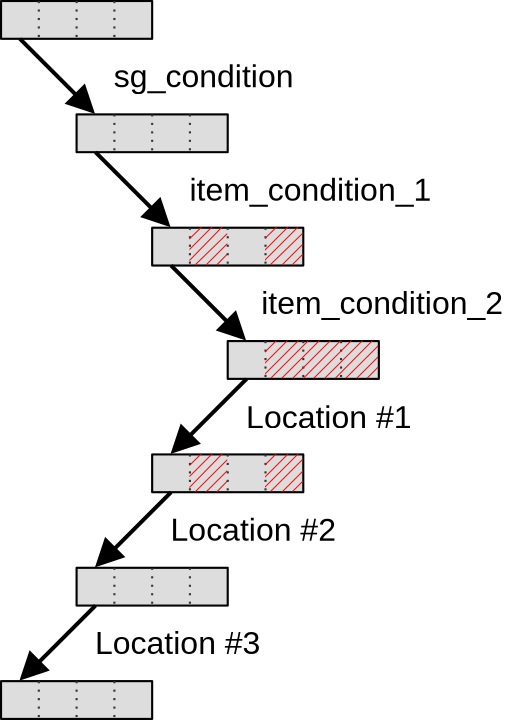

Therefore, we will take the second option: even though the spatial distribution of subgroups within our grid of work-items looks like this from the GPU API’s perspective…

…we will actually decompose each subgroup such that its edge elements only participate in input loading and shuffling, leaving the rest of the simulation work to central elements only:

And then we will make the input region of subgroups overlap with each other, so that their output regions end up being contiguous, as with our previous 2D workgroup layout for shared memory:

At this point, you may reasonably wonder whether this is actually a performance improvement. After all, on the above illustrations, we turned subgroups that produced 4 data points into subgroups that only produce 2 data points by removing one element on each edge, and thus lost ~half or our computing resources during a large fraction of the simulation computation!

But the above schematics were made for clarity, not realism. A quick trip to the GPUinfo database will tell you that in the real world, ~96% of Vulkan implementations that are true GPUs (not CPU emulations thereof) use a subgroup size of 32 or more, with 32 being by far the most common case.

Given subgroups of 32 work-items, reserving two work-items on the edges for input loading tasks only sacrifices <10% of available computing throughput…

…and thus a visual representation of two 32-elements subgroups that overlap with each other, while less readable and amenable to detailed explanations, certainly looks a lot less concerning:

Knowing this, we will hazard the guess that if using subgroups offers a significant speedup over loading data from VRAM and the GPU cache hierarchy (which remains to be proven), it will likely be worth the loss of two work items per subgroup on most common hardware.

And if benchmarking on less common configurations with small subgroups later reveals that this subgroup usage pattern does not work for them, as we suspect, then we will be able to handle this by simply bumping the hardware requirements of our subgroup-based algorithms, so that they are only used when sufficiently large subgroups are available.

Ill-defined reconvergence

Finally, there is one last subgroup gotcha that will not be a very big problem for us, but spells trouble for enough other subgroup-based algorithms that it is worth discussing here.

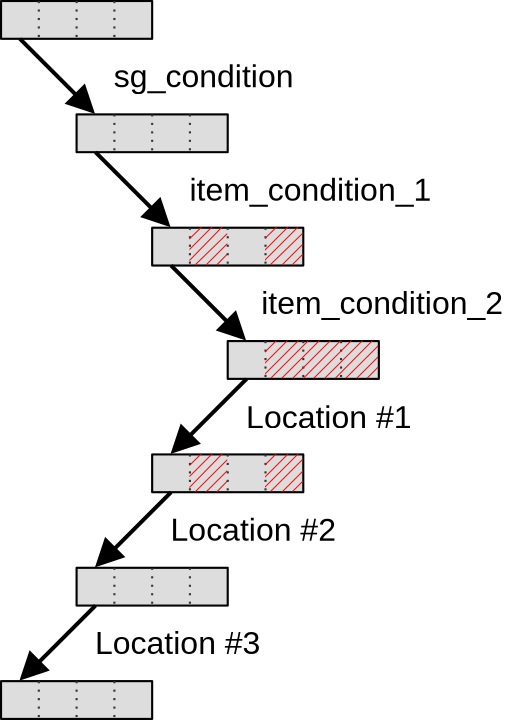

Consider the following GLSL conditional execution pattern:

void main() {

// Entire workgroup is active here

if (sg_condition) {

// Some subgroups are inactive here, others are fully active

// i.e. sg_condition has the same value for all work-items of each subgroup

if (item_condition_1) {

// Some work-items of a subgroup are masked out by item_condition_1 here

// i.e. item_condition is _not_ homogeneous across some subgroups

if (item_condition_2) {

// More work-items are masked out by item_condition_2 here

// i.e. item_condition_2 is _not_ homogeneous even across those

// work-items for which item_condition_1 is true.

}

// Now let's call this code location #1...

}

// ...this code location #2...

}

// ...and this code location #3

}

As this compute shader executes, subgroups within a compute workgroup will reach

the first condition sg_condition. Subgroups for which this condition is false

will skip over this if statement and move directly to code location #3.

So far, this is not a very concerning situation, because SIMD units remain fully

utilized without predication masking out lanes. The only situation where such

conditional branching could possibly be a problem is if sg_condition is only

true for a few sugroups, which can lead to compute units becoming under-utilized

as most subgroups exit early while the remaining one keep blocking the GPU from

moving on to the next (dependent) compute dispatch.

But after this first conditional statement, subgroups for which sg_condition

is true reach the item_condition_1 condition, which can only be handled

through SIMD predication. And then…

- SIMD unit utilization efficiency decreases because while the SIMD lanes for

which

item_condition_1is true keep working, the remaining SIMD lanes remain idle, waiting for the end of theif (item_condition_1)block to be reached before resuming execution. - Some subgroup operations like relative shuffles start behaving weirdly because they operate on data from SIMD lanes that have been masked out, resulting in undefined results. Generally speaking, subgroup operations must be used with care in this situation.

In the GPU world, this scenario is called divergent execution, and it is a very common source of performance problems. But as you can see, in the presence of subgroup operations, it can become a correctness problem too.

In any case, after this execution proceeds and we reach item_condition_2,

which makes the problem worse, but does not fundamentally change the situation.

But the most interesting question is what happens next, at the end of the if

statements?

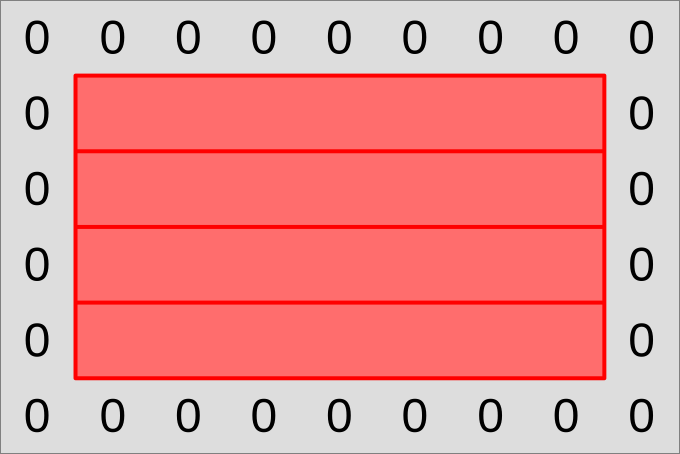

Many GPU programmers new to subgroups naively expect that as soon as an if

statement ends, the subgroup will immediately get back to its state before the

if statement started, with previously disabled work-items re-enabled, as

illustrated below…

…but the Vulkan 1.1 specification does not actually guarantee this and allows

implementations to keep subgroups in a divergent state until the end of the

first if statement that was taken by the entire workgroup. Which in our case

is program location #3, after the end of the initial if (sg_subgroup)

statement.

Until this point of the program is reached, Vulkan implementations are free to keep executing statements multiple times with divergent control flow if they so desire, as illustrated below:

The reason why Khronos decided to allow this behavior in Vulkan 1.1 is not fully clear. Perhaps there are devices on which switching subgroups between a predicated and non-predicated state is expensive, in which case the above scheme could be more efficient in situations where there is little code at locations #1 and #2? But in any case, this implementor freedom makes usage of subgroup operations inside of conditional statements more fraught with peril than it should be.

In an attempt to reduce this peril, several Vulkan extensions were therefore proposed, each exposing a path towards saner subgroup reconvergence behavior on hardware that supports it.

At first, in 2020, the VK_KHR_shader_subgroup_uniform_control_flow extension

was introduced. This extension guarantees that if conditional statements in the

GLSL code are manually annotated as being uniform across entire subgroups, then

subgroup control flow will be guaranteed to reconverge no later than at the end

of the first control flow statement that was not subgroup-uniform. In other

words, when using this extension with suitable code annotations, we have a

guarantee that subgroups will reconverge at code location #2 as illustrated

below:

For some subgroup-based algorithms, however, that guarantee is still not enough,

which is why in 2021 a stricter VK_KHR_shader_maximal_reconvergence extension

was released. This new extension guarantees that if it is enabled, and entire

SPIR-V shader modules are annotated with a suitable attribute, then within these

shader modules subgroups will reconverge as much as possible at the end of each

conditional statement, getting us back to the programmer intuition we started

with:

However, as of 2025, these two Vulkan extensions are quite far from having universal hardware & driver support, and therefore all Vulkan code that aims for broad hardware portability should only use them as a fast path while still providing a fallback code path that is very careful about using subgroup operations inside of conditional statements.

And in doing so, one should also keep in mind that although the above

explanation was given in terms of nested if statements, the same principles

hold for any kind of control flow divergence across a subgroup, including

switch statements with a value that varies across work-items, for loops with

a number of iteration that varies across work items, and a ? b : c ternary

operators.

Thankfully, as you will see later in this chapter, this particular Vulkan specification issue will not affect our Gray-Scott reaction simulation much, because it has little conditional logic in it and the one that we do have will not do too much harm. It is only mentioned in this course as an important subgroup gotcha that you should be aware of when you will consider using Vulkan subgroup operations in more complex GPU computations.

First implementation: 1D workgroups

Mapping GPU work-items to data

To make the migration towards subgroups easier, we will start with a simple mapping of the dataset to GPU workgroups. First of all, we will cut the output region of the simulation domain into lines that are one data point tall…

…and have each output line be processed by a workgroup that also has a line shape:

These 1D workgroups will then be further subdivided by the GPU into 1D subgroups, that we will each make responsible for producing one chunk of the workgroup output.

However, we will not follow the naive chunking of workgroups into subgroups that the GPU’s standard work-item grid hints us into. As explained earlier, our subgroups will overlap with each other, as the input region of each subgroup will extend one data point left and right into the output region of the neighboring subgroup. This will let us get our left and right neighbor value through relative shuffles, without conditional memory loads that would ruin our SIMD efficiency.

As in previous simulation implementations, we will need to be careful with subgroups that reside on the edge of the simulation domain:

- The rightmost work-items may reside beyond the edges of the simulation domain

and should not load input data from the

(U, V)input dataset. - If this happens, the work-item that plays the role of the right input neighbor and is only used for data loading may not be the last work-item of the subgroup.

- With larger workgroups, we may even get entire subgroups that extend outside of the simulation domain. We will have to make those exit early without using them at all.

Finally, our diffusion gradient computation will need top and bottom data points, which we can get through a variation of the same strategy:

- Load a whole line of inputs above/below the output region using the entire subgroup. This will give each work-item that produces an output value its top/bottom neighbor value

- Use relative shuffle operations to get topleft/topright values from the neighboring top value, and bottomleft/bottomright neighbor values from the neighboring bottom value.

Overall, the full picture will look like the illustration below: rows of output that are hierarchically subdivided into workgroups then subgroups, with supporting memory loads around the edge and some out-of-bounds work-items to take care of on the right edge (but not on the bottom edge).

Forcing the use of 1D workgroups

To implement the above scheme, we must first modify our simulation so that it only allows the use of 1D workgroups. This can be done in three steps:

- Revert changes from the shared memory chapter. This 1D workgroup layout is incompatible with our current shared memory scheme, which requires workgroups to have at least three rows. Later in this chapter, we will see how to use shared memory again without needing 2D workgroups of undefined subgroup layout.

- Remove the

workgroup_rowsfield of thePipelineOptionsstruct, replacing each use in the code of with the literal integer1or removing it as appropriate. While we are at it, consider also renaming theworkgroup_colsfield toworkgroup_sizeand adjusting each use in the code as appropriate, this will come in handy later on. - Rework the top-level loop of the

simulatebenchmark so that instead of instead of iterating over[workgroup_cols, workgroup_rows]pairs, it iterates over one-dimensional work-group sizes of[64, 128, 256, 512, 1024]. You will also need to adjust the benchmark group name format string to"run_simulation/workgroup{workgroup_size}/domain{num_cols}x{num_rows}/total{total_steps}".

After this is done, consider doing doing a microbenchmark run to see how switching to 1D workgroups affected benchmark performance. If your GPU is like the author’s Radeon 5600M, you should observe that when going from 2D square-ish workgroups to 1D workgroups with the same number of work-items, the performance impact ranges from neutral to positive.

The fact that on this particular GPU/driver combination, 2D workgroups are not actually helpful to performance, in spite of having better theoretical cache locality properties, suggests that AMD GPUs happens to schedule workgroups in such a way that good cache locality is achieved anyway.8 But we will later see how to guarantee good cache locality without relying on lucky scheduling like this.

On the solution branch, we also performed a GPU pipeline refactor to remove

the now-unused WORKGROUP_ROWS GLSL specialization constant, rename

WORKGROUP_COLS to WORKGROUP_SIZE, and shift specialization constant IDs by

one place to make them contiguous again…

// Configurable workgroup size, as before

layout(local_size_x = 64, local_size_y = 1) in;

layout(local_size_x_id = 0) in;

layout(constant_id = 0) const uint WORKGROUP_SIZE = 64;

// Concentration table width

layout(constant_id = 1) const uint UV_WIDTH = 1920;

// "Scalar" simulation parameters

layout(constant_id = 2) const float FEED_RATE = 0.014;

layout(constant_id = 3) const float KILL_RATE = 0.054;

layout(constant_id = 4) const float DELTA_T = 1.0;

// [ ... subtract 1 from all other constant_id, adapt host code ... ]

…but that’s a bit annoying for only a slight improvement in code readability,

so do not feel forced to do it. If you don’t do it, the only bad consequence is

that you will need to replace future occurences of WORKGROUP_SIZE in the

code samples with the old WORKGROUP_COLS name.

New compute pipeline

Subgroup operations are not part of the core GLSL specification, they are part

of the GL_KHR_shader_subgroup

extension.

To be more precise, we are going to need the

GL_KHR_shader_subgroup_shuffle_relative GLSL extension, which itself is

defined by the GL_KHR_shader_subgroup GLSL extension specification.

We can check can check if the GLSL extension is supported by our GLSL compiler

using a GLSL preprocessor define with the same name, and if so enable it using

the #extension directive…

#ifdef GL_KHR_shader_subgroup_shuffle_relative

#extension GL_KHR_shader_subgroup_shuffle_relative : require

#endif

…but unfortunately, such checking is not very useful in a Vulkan world, as it only checks for extension support within our GLSL compiler. This compiler is only used at application build time to generate a SPIR-V binary that the device driver will later consume at runtime, and it is the feature support of this device that we are actually interested in, but cannot probe from the GLSL side.

In principle, we could work around this by keeping two versions of our compute shader around, one that uses subgroups that doesn’t, but given that…

- Vulkan 1.1 is supported by 98.2% of devices whose Vulkan support was reported to GPUinfo in the past 2 years. Of those, 99.3% support relative shuffle operations and 98.9% have a subgroup size of 4 or more that is compatible with our minimal requirements.

- Juggling between two versions of a shader depending on which features a Vulkan device supports, where one shader version will almost never be exercised and is thus likely to bitrot over future software maintenance, feels excessive for a pedagogical example.

…we will bite the bullet and unconditionally require relative subgroup shuffle support.

// To be added to exercises/src/grayscott/step.comp, after #version

#extension GL_KHR_shader_subgroup_shuffle_relative : require

However, in the interest of correctness, we will later check on the host that the device meets our requirements, and abort the simulation if it doesn’t.

In any case, as in the shared memory chapter, we will need some logic to check whether our work-item is tasked with producing an output data point, and if so where that data point is located within the simulation domain. The mathematical formula changes, but the idea remains the same.

// To be added to exercises/src/grayscott/tep.comp, after #include

// Number of input-only work-items on each side of a subgroup

const uint BORDER_SIZE = 1;

// Maximal number of output data points per subgroup

//

// Subgroups on the edge of the simulation domain may end up processing fewer

// data points.

uint subgroup_output_size() {

return gl_SubgroupSize - 2 * BORDER_SIZE;

}

// Truth that this work-item is within the output region of the subgroup

//

// Note that this is a necessary condition for emitting output data, but not a

// sufficient one. work_item_pos() must also fall inside of the output region

// of the simulation dataset, before data_end_pos().

bool is_subgroup_output() {

return (gl_SubgroupInvocationID >= BORDER_SIZE)

&& (gl_SubgroupInvocationID < BORDER_SIZE + subgroup_output_size());

}

// Maximal number of output data points per workgroup (see above)

uint workgroup_output_size() {

return gl_NumSubgroups * subgroup_output_size();

}

// Position of the simulation dataset that corresponds to the central value

// that this work-item will eventually write data to, if it ends up writing

uvec2 work_item_pos() {

const uint first_x = DATA_START_POS.x - BORDER_SIZE;

const uint item_x = gl_WorkGroupID.x * workgroup_output_size()

+ gl_SubgroupID * subgroup_output_size()

+ gl_SubgroupInvocationID

+ first_x;

const uint item_y = gl_WorkGroupID.y + DATA_START_POS.y;

return uvec2(item_x, item_y);

}

What is new to this chapter, however, is that we will now also have a pair of

utility functions that let us shuffle (U, V) data pairs from one work-item of

the subgroup to another, using the only relative shuffle patterns that we care

about in this simulation:

// To be added to exercises/src/grayscott/step.comp, between above code & main()

// Data from the work-item on the right in the current subgroup

//

// If there is no work-item on the right, or if it is inactive, the result will

// be an undefined value.

vec2 shuffle_from_right(vec2 data) {

return vec2(

subgroupShuffleDown(data.x, 1),

subgroupShuffleDown(data.y, 1)

);

}

// Data from the work-item on the left in the current subgroup

//

// If there is no work-item on the left, or if it is inactive, the result will

// be an undefined value.

vec2 shuffle_from_left(vec2 data) {

return vec2(

subgroupShuffleUp(data.x, 1),

subgroupShuffleUp(data.y, 1)

);

}

After this, our simulation shader entry point will, as usual, begin by assigning a spatial location to the active work-item and loading the associated data value.

Since we have stopped using shared memory for now, we can make work-items that cannot load data from their assigned location exit early.

void main() {

// Map work items into 2D dataset, discard those outside input region

// (including padding region).

const uvec2 pos = work_item_pos();

if (any(greaterThanEqual(pos, padded_end_pos()))) {

return;

}

// Load central value

const vec2 uv = read(pos);

// [ ... rest of the shader follows ... ]

After this, we will begin the diffusion gradient computation, iterating over lines of input as usual.

But instead of iterating over columns immediately after that, we will proceed to set up storage for a full line of three inputs (left neighbor, central value, and right neighbor), and load the central value at our work item’s assigned horizontal position.

// Compute the diffusion gradient for U and V

const uvec2 top = pos - uvec2(0, 1);

const mat3 weights = stencil_weights();

vec2 full_uv = vec2(0.0);

for (int y = 0; y < 3; ++y) {

// Read the top/center/bottom value

vec2 stencil_uvs[3];

stencil_uvs[1] = read(top + uvec2(0, y));

// [ ... rest of the diffusion gradient computation follows ... ]

The left and right neighbor values will then be obtained via shuffle operations. As the comment above these operations highlights, these shuffles will return invalid values for some work-items, but that’s fine because these work-items will not produce outputs. They are only used for the purpose of loading and shffling inputs.

// Get the left/right value from neighboring work-items

//

// This will be garbage data for the work-items on the left/right edge

// of the subgroup, but that's okay, we'll filter these out with an

// is_subgroup_output() condition later on.

//

// It can also be garbage on the right edge of the simulation domain

// where the right neighbor has been rendered inactive by the

// padded_end_pos() filter above, but if we have no right neighbor we

// are only loading data from the zero edge of the simulation dataset,

// not producing an output. So our garbage result will be masked out by

// the other pos < data_end_pos() condition later on.

stencil_uvs[0] = shuffle_from_left(stencil_uvs[1]);

stencil_uvs[2] = shuffle_from_right(stencil_uvs[1]);

// [ ... rest of the diffusion gradient computation follows ... ]

The diffusion gradient computation will then proceed as usual for the current line of inputs, and the whole cycle will repeat for our three lines of input…

// Add associated contributions to the stencil

for (int x = 0; x < 3; ++x) {

full_uv += weights[x][y] * (stencil_uvs[x] - uv);

}

}

// [ ... rest of the computation follows ... ]

…at which point we will be done with the diffusion gradient computation.

After this computation, we know won’t need the left/right work-items from the subgroup anymore (which computed garbage from undefined shuffle outputs anyway), so we can dispose of them.

// Discard work items that are out of bounds for output production work, or

// that received garbage at the previous shuffling stage.

if (!is_subgroup_output() || any(greaterThanEqual(pos, data_end_pos()))) {

return;

}

// [ ... rest of the computation is unchanged ... ]

And beyond that, the rest of the simulation shader will not change.

If you try to compile the simulation program at this stage, you will notice that

our shaderc GLSL-to-SPIRV compiler is unhappy because we are using subgroup

operations, which require a newer SPIR-V version than what vulkano requires by

default.

It is okay to change this in pipeline.rs, in doing so we are not bumping our

device requirements further than we already did by deciding to mandate Vulkan

1.1 earlier:

// To be changed in exercises/src/grayscott/pipeline.rs

/// Shader modules used for the compute pipelines

mod shader {

vulkano_shaders::shader! {

spirv_version: "1.3", // <- This is new

shaders: {

init: {

ty: "compute",

path: "src/grayscott/init.comp"

},

step: {

ty: "compute",

path: "src/grayscott/step.comp"

},

}

}

}New device requirements

By going the lazy route of mandating subgroup shuffle support, we gained a few

device support requirements. We will therefore encode them into a utility

function at the root of the grayscott code module…

// To be added to exercises/src/grayscott/mod.rs

use vulkano::{

device::physical::{PhysicalDevice, SubgroupFeatures},

Version,

};

/// Check that the selected Vulkan device meets our requirements

pub fn is_suitable_device(device: &PhysicalDevice) -> bool {

let properties = device.properties();

device.api_version() >= Version::V1_1

&& matches!(

properties.subgroup_supported_operations,

Some(ops) if ops.contains(SubgroupFeatures::SHUFFLE_RELATIVE)

)

&& matches!(

properties.subgroup_size,

Some(size) if size >= 3

)

}…check that these requirements are met at the beginning of

run_simulation()…

// To be changed in exercises/src/grayscott/mod.rs

/// Simulation runner, with a user-specified output processing function

pub fn run_simulation<ProcessV: FnMut(ArrayView2<Float>) -> Result<()>>(

options: &RunnerOptions,

context: &Context,

process_v: Option<ProcessV>,

) -> Result<()> {

// Check that the selected Vulkan device meets our requirements

assert!(

is_suitable_device(context.device.physical_device()),

"Selected Vulkan device does not meet the Gray-Scott simulation requirements"

);

// [ ... rest of the function is unchanged ... ]

}…and modify the Vulkan context’s default device selection logic (when the user does not explicitly pick a Vulkan device) to select a device that meets those requirements:

// To be changed in exercises/src/context.rs

/// Pick a physical device

fn select_physical_device(

instance: &Arc<Instance>,

options: &DeviceOptions,

quiet: bool,

) -> Result<Arc<PhysicalDevice>> {

let mut devices = instance.enumerate_physical_devices()?;

if let Some(index) = options.device_index {

// [ ... user-specified device code path is unchanged ... ]

} else {

// Otherwise, choose a device according to its device type

devices

// This filter() iterator adaptor is new

.filter(|dev| crate::grayscott::is_suitable_device(dev))

.min_by_key(|dev| match dev.properties().device_type {

// [ ... device ordering is unchanged ... ]

})

.inspect(|device| {

// [ ... and logging is unchanged ... ]

})

.ok_or_else(|| "no Vulkan device available".into())

}

}Dispatch configuration changes

Finally, we need to adjust the number of work-groups that are spawned in order

to match our new launch configuration. So we adjust the start of the

schedule_simulation() function to compute the new number of workgroups on the

X axis…

// To be changed in exercises/src/grayscott/mod.rs

/// Record the commands needed to run a bunch of simulation iterations

fn schedule_simulation(

options: &RunnerOptions,

context: &Context, // <- Need to add this parameter

pipelines: &Pipelines,

concentrations: &mut Concentrations,

cmdbuild: &mut CommandBufferBuilder,

) -> Result<()> {

// Determine the appropriate dispatch size for the simulation

let subgroup_size = context

.device

.physical_device()

.properties()

.subgroup_size

.expect("Should have checked for subgroup supports before we got here");

let subgroup_output_size = subgroup_size - 2;

let subgroups_per_workgroup = options

.pipeline

.workgroup_size

.get()

.checked_div(subgroup_size)

.expect("Workgroup size should be a multiple of the subgroup size");

let outputs_per_workgroup = subgroups_per_workgroup * subgroup_output_size;

let workgroups_per_row = options.num_cols.div_ceil(outputs_per_workgroup as usize) as u32;

let simulate_workgroups = [workgroups_per_row, options.num_rows as u32, 1];

// [ ... rest of the simulation scheduling is unchanged ... ]

}…and this means that schedule_simulation() now needs to have access to the

Vulkan context, so we pass that new parameter too in the caller of

schedule_simulation(), which is SimulationRunner::schedule_next_output():

// To be changed in exercises/src/grayscott/mod.rs

impl<'run_simulation, ProcessV> SimulationRunner<'run_simulation, ProcessV>

where

ProcessV: FnMut(ArrayView2<Float>) -> Result<()>,

{

// [ ... constructor is unchanged ... ]

/// Submit a GPU job that will produce the next simulation output

fn schedule_next_output(&mut self) -> Result<FenceSignalFuture<impl GpuFuture + 'static>> {

// Schedule a number of simulation steps

schedule_simulation(

self.options,

self.context, // <- This parameter is new

&self.pipelines,

&mut self.concentrations,

&mut self.compute_cmdbuild,

)?;

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]Notice that we have introduced a new condition that the workgroup size be a multiple of the subgroup size. That’s because Vulkan normally allows workgroup sizes not to be a multiple of the subgroup size, by starting one or more subgroups in a state where some SIMD lanes are disabled (in the case of our 1D workgroup, it will be the last lanes). But we don’t want to allow it because…

- It’s inefficient, since the affected subgroup(s) don’t execute at full SIMD throughput.

- It’s hard to support, in our case we would need to replace our simple

is_subgroup_output()GLSL logic with a more complicated one that checks whether we are in the last workgroup and if so adjusts our expectations about what the last subgroup lane should be.

In any case, however well-intentioned, this change is affecting the semantics of a user-visible interface for subgroup size tuning, so we should…

- Document that the workgroup size should be a multiple of the subgroup size in

the CLI help text about

PipelineOptions::workgroup_size. - Adjust the default value of this CLI parameter so that it is guaranteed to always be a multiple of the device’s subgroup size. Since the maximal subgroup size supported by Vulkan is 128, and Vulkan subgroup sizes are guaranteed to be a power of two this means that our default workgroup size should be at least 128, or a multiple thereof.

Overall, the updated PipelineOptions definition looks like this…

// Change in exercises/src/grayscott/pipeline.rs

/// CLI parameters that guide pipeline creation

#[derive(Debug, Args)]

pub struct PipelineOptions {

/// Number of work-items in a workgroup

///

/// Must be a multiple of the Vulkan device's subgroup size.

#[arg(short = 'W', long, default_value = "128")]

pub workgroup_size: NonZeroU32,

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]

}…and you should also remove the microbenchmark configuration for workgroup sizes of 64, which has never performed well anyway.

With that, we are ready to run our first subgroups-enabled simulation. But we still are at the mercy of the device-selected subgroup size for now, which may not be the one that works best for our algorithm. Let’s see how we can fix that next.

Using subgroup size control

As mentioned earlier, subgroup size control was first specified as a

VK_EXT_subgroup_size_control extension to Vulkan 1.1, and later integrated

into the core Vulkan 1.3 specification. However, at the time of writing, the

vulkano Rust bindings that we are using only support the Vulkan 1.3 version of

this specification. We will therefore only support subgroup size control for

Vulkan 1.3 devices.

There are two key parts to using Vulkan 1.3 subgroup size control:

- Because it is an optional device feature, we must first enable it at the time

where a logical

Deviceis created, via theenabled_featuresfield of theDeviceCreateInfostruct.- As this is a Vulkan 1.3 specific feature, and Vulkan 1.3 is far from being universally supported at the time of writing, we will not want to force this feature on. It should either be enabled by explicit user request, or opportunistically when the device supports it.

- Given a Vulkan device for which subgroup size control has been enabled, the

subgroup size of a compute pipeline can then be set at construction time by

setting the

required_subgroup_sizefield of the associatedPipelineShaderStageCreateInfo. In doing so, we must respect the rules outlined in the documentation ofrequired_subgroup_size:- The user-specified subgroup size must be a power of two ranging between the

min_subgroup_sizeandmax_subgroup_sizedevice limits. These device limits were added to the device properties by Vulkan 1.3, which from avulkanoperspective means that the associated optional fields ofDevicePropertieswill always be set on Vulkan 1.3 compliant devices. - Compute pipeline workgroups must not contain more subgroups than dictated by

the Vulkan 1.3

max_compute_workgroup_subgroupsdevice limit. This new limit supplements themax_compute_work_group_invocationslimit that had been present since Vulkan 1.0 by acknowledging the fact that one some devices, the maximum work group size is specified as a number of subgroups, and is thus subgroup size dependent.

- The user-specified subgroup size must be a power of two ranging between the

Enabling device support + context building API refactor

Having to enable a device feature first is a bit of an annoyance in the

exercises codebase layout, because it means that our new subgroup size setting

(which is a parameter of compute pipeline building in the Gray-Scott simulation)

will end up affecting device building (which is handled by our Vulkan context

building code, which we’ve been trying to keep quite generic so far).

And this in turn means that we will once again need to add a parameter to the

Context::new() constructor and adapt all of its clients, including our old

square program that does not use subgroup size control. Clearly, this is not

great API design, so let’s give our Context constructor a quick round of API

redesign that reduces the need for such client adaptations in the future.

All of the Context constructor parameters that we have been adding over time

represent optional Vulkan context features that have an obvious default setting:

- The

quietparameter inhibits logging for microbenchmarks. Outside of microbenchmarks, logging should always be enabled, so that is a fine default setting. - The

progressparameter makes logging interoperate nicely with theindicatifprogress bars, which are only used by thesimulatebinary. Outside of thesimulatebinary and other future programs withindicatifprogress bar, there is no need to accomodateindicatif’s constraints and we should log tostderrdirectly.

As you’ve seen before in the vulkano API, a common way to handle this sort of

“parameters with obvious defaults” in Rust is to pack them into a struct with a

default value…

/// `Context` configuration that is decided by the code that constructs the

/// context, rather than by the user (via environment or CLI)

#[derive(Clone, Default)]

pub struct ContextAppConfig {

/// When set to true, this boolean flag silences all warnings

pub quiet: bool,

/// When this is configured with an `indicatif::ProgressBar`, any logging

/// from `Context` will be printed in an `indicatif`-aware manner pub

progress: Option<ProgressBar>,

// [ ... subgroup size control enablement coming up ... ]

}…then make it a parameter to the function of interest and later, on the client side, override only the parameters of interest and use the default value for all other fields:

// Example of ContextAppConfig configuration from a microbenchmark

ContextAppConfig {

quiet: true,

..Default::default()

}The advantage of doing this this way is that as we later add support for new context features, like subgroup size control, existing clients will not need to be changed as long as they do not need the new feature. And in this way, API backwards compatibility will be achieved.

In our case, we know ahead of time that we are going to want an extra parameter to control subgroup size control, so let’s do it right away:

// Add to exercises/src/context.rs

/// `Context` configuration that is decided by the code that constructs the

/// context, rather than by the user (via environment or CLI)

#[derive(Clone, Default)]

pub struct ContextAppConfig {

/// When set to true, this boolean flag silences all warnings

pub quiet: bool,

/// When this is configured with an `indicatif::ProgressBar`, any logging

/// from `Context` will be printed in an `indicatif`-aware manner

pub progress: Option<ProgressBar>,

/// Truth that the Vulkan 1.3 `subgroupSizeControl` feature should be

/// enabled (requires Vulkan 1.3 device with support for this feature)

pub subgroup_size_control: SubgroupSizeControlConfig,

}

/// Truth that the `subgroupSizeControl` Vulkan extension should be enabled

#[derive(Copy, Clone, Default, Eq, PartialEq)]

pub enum SubgroupSizeControlConfig {

/// Do not enable subgroup size control

///

/// This is the default and requires no particular support from the device.

/// But it prevents `subgroupSizeControl` from being used.

#[default]

Disable,

/// Enable subgroup size control if supported

///

/// Code that uses this configuration must be prepared to receive a device

/// that may or may not support subgroup size control.

IfSupported,

/// Always enable subgroup size control

///

/// Device configuration will fail if the user requests a device that does

/// not support subgroup size control, or if autoconfiguration does not find

/// a device that supports it.

Enable,

}As you can see, we are going to want to support three subgroup size control configurations:

- Do not enable subgroup size control. This is the default, and it suits old

clients that don’t use subgroup size control like the

squarecomputation very well. - Enable subgroup size control if it is supported, otherwise ignore it. This configuration is perfect for microbenchmarks, which want to exercise multiple subgroup sizes if available, without dropping support for devices that do not support Vulkan 1.3.

- Unconditionally enable subgroup size control. This is the right thing to do if the user requested that a specific subgroup size be used.

We will then refactor our Context::new() constructor to use the new

ContextAppConfig struct instead of raw parameters, breaking its API one last

time, and adjust downstream functions to pass down this struct or individual

members thereof as appropriate.

// To be changed in exercises/src/context.rs

impl Context {

/// Set up a `Context`

pub fn new(options: &ContextOptions, app_config: ContextAppConfig) -> Result<Self> {

let library = VulkanLibrary::new()?;

let mut logging_instance =

LoggingInstance::new(library, &options.instance, app_config.progress.clone())?;

let physical_device =

select_physical_device(&logging_instance.instance, &options.device, &app_config)?;

let DeviceAndQueues {

device,

compute_queue,

transfer_queue,

} = DeviceAndQueues::new(physical_device, &app_config)?;

// [ ... rest of context building does not change ... ]

}

}This means that select_physical_device() now takes a full app_config instead

of a single quiet boolean parameter:

/// Pick a physical device

fn select_physical_device(

instance: &Arc<Instance>,

options: &DeviceOptions,

app_config: &ContextAppConfig,

) -> Result<Arc<PhysicalDevice>> {

// [ ... change all occurences of `quiet` to `app_config.quiet` here ... ]

}And there is a good reason for this, which is that if the user explicitly

required subgroup size control with SubgroupSizeControlConfig::Enable, our

automatic device selection logic within this function must adapt. Otherwise, we

could accidentally select a device that does not support subgroup size control

even if there’s another device on the machine that does, resulting in an

automatic device configuration that errors out when it could not do so.

We handle that by having around a new function that tells if a Vulkan device supports subgroup size control for compute shaders…

// Add to exercises/src/context.rs

use vulkano::{shader::ShaderStages, Version};

/// Check for compute shader subgroup size control support

pub fn supports_compute_subgroup_size_control(device: &PhysicalDevice) -> bool {

if device.api_version() < Version::V1_3 {

return false;

}

if !device.supported_features().subgroup_size_control {

return false;

}

device

.properties()

.required_subgroup_size_stages

.expect("Checked for Vulkan 1.3 support above")

.contains(ShaderStages::COMPUTE)

}…and adding this check to our device filter within select_physical_device(),

which formerly only checked that subgroup support was good enough for our

Gray-Scott simulation:

// Change in exercises/src/context.rs

/// Pick a physical device

fn select_physical_device(

instance: &Arc<Instance>,

options: &DeviceOptions,

app_config: &ContextAppConfig,

) -> Result<Arc<PhysicalDevice>> {

let mut devices = instance.enumerate_physical_devices()?;

if let Some(index) = options.device_index {

// [ ... known-device logic is unchanged ... ]

} else {

// Otherwise, choose a device according to its device type

devices

.filter(|dev| {

if !crate::grayscott::is_suitable_device(dev) {

return false;

}

if app_config.subgroup_size_control == SubgroupSizeControlConfig::Enable

&& !supports_compute_subgroup_size_control(dev)

{

return false;

}

true

})

// [ ... rest of the iterator pipeline is unchanged ... ]

}

}Finally, we make DevicesAndQueues::new() enable subgroup size control as

directed…

impl DeviceAndQueues {

/// Set up a device and associated queues

fn new(device: Arc<PhysicalDevice>, app_config: &ContextAppConfig) -> Result<Self> {

// [ ... queue selection is unchanged ... ]

// Decide if the subgroupSizeControl Vulkan feature should be enabled

let subgroup_size_control = match app_config.subgroup_size_control {

SubgroupSizeControlConfig::Disable => false,

SubgroupSizeControlConfig::IfSupported => {

supports_compute_subgroup_size_control(&device)

}

SubgroupSizeControlConfig::Enable => true,

};

let enabled_features = DeviceFeatures {

subgroup_size_control,

..Default::default()

};

// Set up the device and queues

let (device, mut queues) = Device::new(

device,

DeviceCreateInfo {

queue_create_infos,

enabled_features,

..Default::default()

},

)?;

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]

}

}…and as far as the context-building code is concerned, we are all set.

Finally, we switch the square binary and microbenchmark to the new

Context::new() API for what will hopefully be the last time.

// Change in exercises/src/bin/square.rs

use grayscott_exercises::context::ContextAppConfig;

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Parse command line options

let options = Options::parse();

// Set up a Vulkan context

let context = Context::new(&options.context, ContextAppConfig::default())?;

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]

}

// Change in exercises/benches/square.rs

use grayscott_exercises::context::ContextAppConfig;

// Benchmark for various problem sizes

fn criterion_benchmark(c: &mut Criterion) {

// Iterate over device numbers, stopping on the first failure (which we

// take as evidence that no such device exists)

for device_index in 0.. {

let context_options = ContextOptions {

instance: InstanceOptions { verbose: 0 },

device: DeviceOptions {

device_index: Some(device_index),

},

};

let app_config = ContextAppConfig {

quiet: true,

..Default::default()

};

let Ok(context) = Context::new(&context_options, app_config.clone()) else {

break;

};

// Benchmark context building

let device_name = &context.device.physical_device().properties().device_name;

c.bench_function(&format!("{device_name:?}/Context::new"), |b| {

b.iter(|| {

Context::new(&context_options, app_config.clone()).unwrap();

})

});

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]

}

}Let’s not adapt the Gray-Scott binary and benchmark to this API yet, though. We

have other things to do on that side before we can set that new

subgroup_size_control parameter correctly.

Simulation subgroup size control

In the Gray-Scott simulation’s pipeline module, we will begin by adding a new

optional simulation CLI parameter for explicit subgroup size control, which can

also be set via environment variables for microbenchmarking convenience. This is

just a matter of adding a new field to the PipelineOptions struct with the

right annotations:

// Change in exercises/src/grayscott/pipeline.rs

/// CLI parameters that guide pipeline creation

#[derive(Debug, Args)]

pub struct PipelineOptions {

/// Number of work-items in a workgroup

#[arg(short = 'W', long, default_value = "64")]

pub workgroup_size: NonZeroU32,

/// Enforce a certain number of work-items in a subgroup

///

/// This configuration is optional and may only be set on Vulkan devices

/// that support the Vulkan 1.3 `subgroupSizeControl` feature.

#[arg(env, short = 'S', long)]

pub subgroup_size: Option<NonZeroU32>,

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]

}We will then adjust our compute stage setup code so that it propagates this configuration to our compute pipelines when it is present…

/// Set up a compute stage from a previously specialized shader module

fn setup_compute_stage(

module: Arc<SpecializedShaderModule>,

options: &PipelineOptions, // <- Need this new parameter

) -> PipelineShaderStageCreateInfo {

let entry_point = module

.single_entry_point()

.expect("a compute shader module should have a single entry point");

PipelineShaderStageCreateInfo {

required_subgroup_size: options.subgroup_size.map(NonZeroU32::get),

..PipelineShaderStageCreateInfo::new(entry_point)

}

}…which means the pipeline options must be passed down to

setup_compute_stage() now, so the Pipelines::new() constructor needs a small

adjustment:

impl Pipelines {

pub fn new(options: &RunnerOptions, context: &Context) -> Result<Self> {

fn setup_stage_info(

options: &RunnerOptions,

context: &Context,

load: impl FnOnce(

Arc<Device>,

)

-> std::result::Result<Arc<ShaderModule>, Validated<VulkanError>>,

) -> Result<PipelineShaderStageCreateInfo> {

// [ ... beginning is unchanged ... ]

Ok(setup_compute_stage(module, &options.pipeline))

}

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]

}

}We must then adjust the simulation scheduling code so that it accounts for the subgroup size that is actually being used, which is not necessarily the default subgroup size from Vulkan 1.1 device properties anymore…

// Change in exercises/src/grayscott/mod.rs

/// Record the commands needed to run a bunch of simulation iterations

fn schedule_simulation(

options: &RunnerOptions,

context: &Context,

pipelines: &Pipelines,

concentrations: &mut Concentrations,

cmdbuild: &mut CommandBufferBuilder,

) -> Result<()> {

// Determine the appropriate dispatch size for the simulation

let subgroup_size = if let Some(subgroup_size) = options.pipeline.subgroup_size {

subgroup_size.get()

} else {

context

.device

.physical_device()

.properties()

.subgroup_size

.expect("Should have checked for subgroup supports before we got here")

};

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]

}…and we must adjust the main simulation binary so that during the Vulkan

context setup stage, it requests support for subgroup size control if the user

has asked for it via the compute pipeline options. We will obviously also

migrate it to the new ContextAppConfig API along the way:

// Change in exercises/src/bin/simulate.rs

use grayscott_exercises::context::ContextAppConfig;

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// [ ... beginning is unchanged ... ]

// Set up the Vulkan context

let context = Context::new(

&options.context,

ContextAppConfig {

progress: Some(progress.clone()),

subgroup_size_control: if options.runner.pipeline.subgroup_size.is_some() {

SubgroupSizeControlConfig::Enable

} else {

SubgroupSizeControlConfig::Disable

},

..Default::default()

},

)?;

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]

}Microbenchmarking at all subgroup sizes

Finally, let us migrate our simulation microbenchmark to use subgroup size control. Here, the behavior that we want is a bit more complex than for the main simulation binary:

- By default, we want to benchmark at all available subgroup sizes if subgroup size control is available. If it is not available, on the other hand, we only benchmark at the default Vulkan 1.1 subgroup size as we did before. This lets us explore the full capabilities of newer devices without increasing our minimal device requirements on the other end.

- Probing all subgroup sizes increases benchmark duration by a multiplicative

factor, which can be very large on some devices (there are embedded GPUs out

there that support all subgroup sizes from 4 to 128). Therefore, once the

optimal subgroup size has been determined, we let the user benchmark at this

subgroup size only via the

SUBGROUP_SIZEenvironment variable (which controls thesubgroup_sizefield of ourPipelineOptionsthroughclapmagic). Obviously, in that case, we will need to force subgroup size control on, as in any other case where the user specifies the desired subgroup size control.

This behavior can be implemented in a few steps. First of all, we adjust the

Vulkan context setup code so that subgroup size control is always enabled if the

user specified an explicit subgroup size, and enabled if supported otherwise.

Along the way, we migrate our Vulkan context setup to the new ContextAppConfig

API:

// Change in exercises/benches/simulate.rs

use grayscott_exercises::context::{

ContextAppConfig,

SubgroupSizeControlConfig,

};

fn criterion_benchmark(c: &mut Criterion) {

// Start from the default context and runner options

let context_options = default_args::<ContextOptions>();

let mut runner_options = default_args::<RunnerOptions>();

// Set up the Vulkan context

let context = Context::new(

&context_options,

ContextAppConfig {

quiet: true,

subgroup_size_control: if runner_options.pipeline.subgroup_size.is_some() {

SubgroupSizeControlConfig::Enable

} else {

SubgroupSizeControlConfig::IfSupported

},

..Default::default()

},

)

.unwrap();

// [ ... other changes coming up next ... ]

}We then set up a Vec of optional explicit subgroup sizes to be benchmarked:

- If subgroup size control is not supported, then there is a single

Noneentry, which models the default subgroup size from Vulkan 1.1. - Otherwise there is one

Some(size)entry per subgroup size that should be exercised.

That approach is admittedly not very elegant, but it will make it easier to support presence or absence of subgroup size control with a single code path later on.

We populate this table according to the logic discussed above: user-specified subgroup size takes priority, then subgroup size control if supported, otherwise default subgroup size.

use grayscott_exercises::context;

// [ ... after Vulkan context setup ... ]

// Determine which subgroup size configurations will be benchmarked

//

// - If the user specified a subgroup size via the SUBGROUP_SIZE environment

// variable, then we will only try this one.

// - Otherwise, if the device supports subgroup size control, then we will

// try all supported subgroup sizes.

// - Finally, if the device does not support subgroup size control, we have

// no choice but to use the default subgroup size only.

let mut subgroup_sizes = Vec::new();

if runner_options.pipeline.subgroup_size.is_some() {

subgroup_sizes.push(runner_options.pipeline.subgroup_size);

} else if context::supports_compute_subgroup_size_control(context.device.physical_device()) {

let device_properties = context.device.physical_device().properties();

let mut subgroup_size = device_properties.min_subgroup_size.unwrap();

let max_subgroup_size = device_properties.max_subgroup_size.unwrap();

while subgroup_size <= max_subgroup_size {

subgroup_sizes.push(Some(NonZeroU32::new(subgroup_size).unwrap()));

subgroup_size *= 2;

}

} else {

subgroup_sizes.push(None);

}

// [ ... more to come ... ]Within the following loop ove workgroup sizes, we then inject a new loop over

benchmarked subgroup sizes. When an explicit subgroup size is specified, our

former device support test is extended to also take the new

max_compute_workgroup_subgroups limit into account. And if the selected

subgroup size is accepted, we inject into the PipelineOptions used by the

benchmark.

// [ ... after subgroup size enumeration ... ]

// For each workgroup size of interest...

for workgroup_size in [64, 128, 256, 512, 1024] {

// ...and for each subgroup size of interest...

for subgroup_size in subgroup_sizes.iter().copied() {

// Check if the device supports this workgroup configuration

let device_properties = context.device.physical_device().properties();

if workgroup_size > device_properties.max_compute_work_group_size[0]

|| workgroup_size > device_properties.max_compute_work_group_invocations

{

continue;

}

if let Some(subgroup_size) = subgroup_size

&& workgroup_size.div_ceil(subgroup_size.get())

> device_properties.max_compute_workgroup_subgroups.unwrap()

{

continue;

}

// Set up the pipeline

runner_options.pipeline = PipelineOptions {

workgroup_size: NonZeroU32::new(workgroup_size).unwrap(),

subgroup_size,

update: runner_options.pipeline.update,

};

// [ ... more to come ... ]

}

}

}Finally, when we configure our criterion benchmark group, we indicate any

explicitly configured subgroup size in the benchmark name so that benchmarks

with different subgroup sizes can be differentiated from each other and filtered

via a regex.

// [ ... at the top of the loop over total_steps ... ]

// Benchmark groups model a certain total amount of work

let mut group_name = format!("run_simulation/workgroup{workgroup_size}");

if let Some(subgroup_size) = subgroup_size {

write!(group_name, "/subgroup{subgroup_size}").unwrap();

}

write!(

group_name,

"/domain{num_cols}x{num_rows}/total{total_steps}"

)

.unwrap();

let mut group = c.benchmark_group(group_name);

group.throughput(Throughput::Elements(

(num_rows * num_cols * total_steps) as u64,

));

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]And that’s it. We are now ready to benchmark our subgroups-enabled simulation at all subgroup sizes supported by our GPU.

First benchmark results

TODO: Check output in wave32 mode and benchmark wrt async-download-1d.

Guaranteeing 2D cache locality

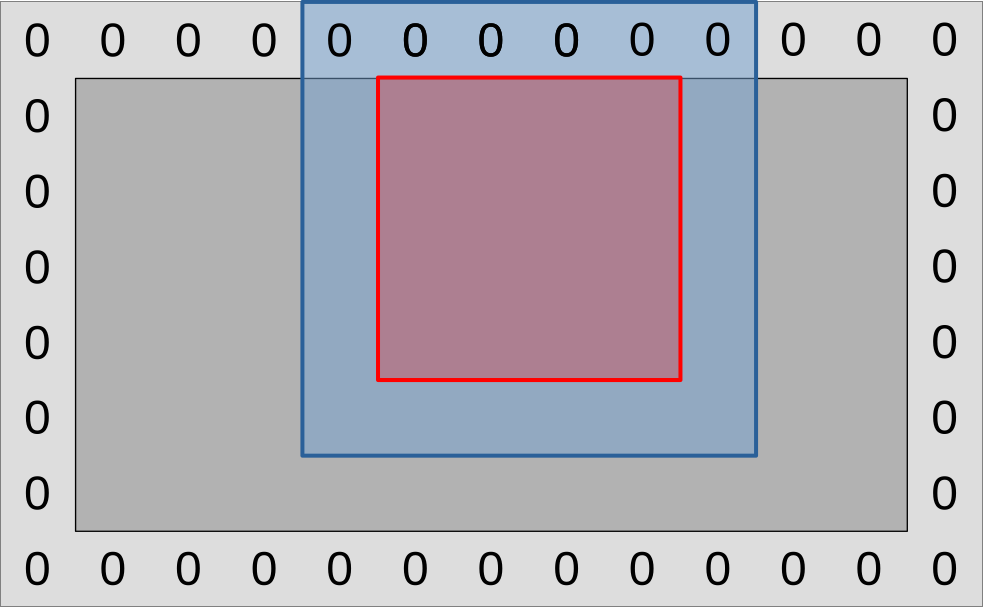

As hinted above, our initial mapping of GPU work-items to data was intended to be easier to understand and make introduction of subgroup operations easier, but it has several flaws:

- From a memory bandwidth savings perspective, subgroup operations give us good reuse of every input data points across left/right neighbors. But our long line-like 1D workgroups do not guarantee much reuse of input datapoints across top/bottom neighbors, hampering cache locality. We may get some cache locality back if the GPU work scheduler happens to schedule workgroups with the same X position and consecutive Y positions on the same compute unit, but that’s just being lucky as nothing in the Vulkan spec guarantees this behavior.

- From an execution efficiency perspective, workgroups that extend far across one spatial direction are not great either, because it is likely that on the right edge they will extend far beyond the end of the simulation domain, and this will reduce in lots of wasted scheduling work (Vulkan device will spawn lots of subgroups/work-items that cannot even load input data and must exit immediately).

Due of these two issues, it would be better for our work-items to cover a simulation domain region that extends over the two dimensions of space, in a shape that gets as close to square as possible.

But as we have seen before, we cannot simply do so by using workgroups that have a 2D shape within the GPU-defined work grid, because when we do that our subgroup spatial layout becomes undefined and we cannot efficiently tell at compile time which work-item within the subgroup is a left/right neighbor of the active work-item anymore.

However, there is a less intuitive way to get where we want, which is to ask for 1D work-groups from the GPU API, but then map them over a 2D spatial region by having each subgroup process a different line of the simulation domain at the GLSL level.

In other words, instead of spatially laying out the subgroups of a workgroup in such a way that their output region forms a contiguous line, as we did before…

…we will now stack their output regions on top of each other, without any horizontal shift:

Now, as the diagram above hints, if we stacked enough sugroups on top of each other like this, we could end up having the opposite problem where our subgroups are very narrow in the horizontal direction. Which in turn could lead to worse cached data reuse across subgroups in the horizontal direction and more wasted GPU scheduler work on the bottom edge of the simulation domain.

But this is unlikely to be a problem for real-world GPUs as of 2025 because…

- As the GPUinfo database told us earlier, most GPUs have a rather wide subgroup size. 32 work-items is the most common configuration as of 2025, while 64 work-items remains quite frequent too due to its use in older AMD GPU architectures.

- 80% of GPUs whose properties were reported to GPUinfo in the past 2 years have a maximal work-group size of 1024 work-items, with a few extending a bit beyond up to 2048 work-items. With a subgroup size of 32 work-items, that’s respectively 32 and 64 subgroups, getting us close to the square-ish shape that is best for cache locality and execution efficiency.

…and if it becomes a problem for future GPUs, we will be able to address it with only slightly more complex spatial layout logic in our compute shaders:

- If subgroups end up getting narrower with respect to workgroups, then we can use a mixture of our old and new strategy to tile subgroups spatially in a 2D fashion, e.g. get 2 overlapping columns of subgroups instead of one single stack.

- If subgroups end up getting wider with respect to workgroups, then we can make a single subgroup process 2+ lines of output by using a more complicated shuffling and masking pattern that treats the subgroup as e.g. a 16x2 row-major rectangle of work-items.9

Sticking with simple subgroup stacking logic for now, the GLSL compute shader

change is pretty straightforward as we only need to adjust the work_item_pos()

function…

// To be changed in exercises/src/grayscott/step.comp

// Position of the simulation dataset that corresponds to the central value

// that this work-item will eventually write data to, if it ends up writing

uvec2 work_item_pos() {

const uint first_x = DATA_START_POS.x - BORDER_SIZE;

const uint item_x = gl_WorkGroupID.x * subgroup_output_size()

+ gl_SubgroupInvocationID

+ first_x;

const uint item_y = gl_WorkGroupID.y * gl_NumSubgroups

+ gl_SubgroupID

+ DATA_START_POS.y;

return uvec2(item_x, item_y);

}

…and on the host size, we need to adjust the compute dispatch size so that it spawns more workgroups on the horizontal axis and less on the vertical axis:

// To be changed in exercises/src/grayscott/mod.rs

/// Record the commands needed to run a bunch of simulation iterations

fn schedule_simulation(

options: &RunnerOptions,

context: &Context,

pipelines: &Pipelines,

concentrations: &mut Concentrations,

cmdbuild: &mut CommandBufferBuilder,

) -> Result<()> {

// [ ... everything up to subgroups_per_workgroup is unchanged ... ]

let workgroups_per_row = options.num_cols.div_ceil(subgroup_output_size as usize) as u32;

let workgroups_per_col = options.num_rows.div_ceil(subgroups_per_workgroup as usize) as u32;

let simulate_workgroups = [workgroups_per_row, workgroups_per_col, 1];

// [ ... rest is unchanged ... ]

}And with just these two changes, we already get a better chance that our compute pipeline will experience good cache locality for loads from all directions, without relying on our GPU to “accidentally” schedule workgroups with consecutive Y coordinates on the same compute unit.

TODO: Add and comment benchmark results

Shared memory, take 2