Introduction

Welcome to this course about high-performance numerical computing with Rust on GPU!

This course builds upon the companion course on CPU

computing, and is meant to

directly follow it. Basic concepts of the Rust programming language will

therefore not be introduced again. Instead, we will see how these concepts can

be leveraged to build high-performance GPU computations, using the

Vulkan API via the vulkano

high-level Rust binding.

These are rather uncommon technological choices in scientific computing, so you may wonder why they were chosen. Rust ecosystem support aside, Vulkan was picked as one of few GPU APIs that manage to avoid the classic design flaws of HPC-centric GPU APIs:

- Numerical computations should aim for maximal portability by default. Nonportable programs are the open-air landfills of HPC: they may seem initially convenient, but come with huge hidden costs and leave major concerns up to future generations.1

- CPU/GPU performance portability doesn’t work. Decades of research have produced nothing but oversized frameworks of mind-boggling complexity where either CPU or GPU performance does not even remotely match that of well-optimized code on non-toy programs. A GPU-first API can be conceptually simpler, more reliable, and ease optimization; all this saves enough time to let you write a good CPU version of your computational kernel if you need one.

- Proprietary API emulation or imitation doesn’t work. Because the monopoly manufacturer controls the API and has much greater software development resources, all other hardware will always be a second-class citizen with lagging support, unstable runtimes, and poor support of advanced hardware features that the monopoly manufacturer didn’t implement.

- Relying on hardware manufacturer good will doesn’t work. Monopoly manufacturers will not help you write code that works on other hardware, and minority hardware manufacturers have little resources to dedicate to obscure HPC portability technologies with low adoption. It is more effective to force the manufacturers’ hand by basing your work on a widely adopted technology whose reach extends far beyond the relatively small HPC community.

As for the vulkano Rust binding specifically, the choice came down to general

maturity, maintenance status, broad Vulkan API coverage, high-quality

documentation, ease of installation and good alignment with the Rust design

goals of making code type/memory/thread-safe by default.

Pedagogical advice given in the introduction of the CPU course still applies:

- This course is meant to be followed in order, environment setup section aside. Each sections will build upon the concepts taught and the exercise work done in earlier sections.

- The material is written to allow further self-study after the school, so it’s okay to fall a little behind the group. Good understanding is more important than full chapter coverage.

- Solutions to some exercises are provided in the top commits of the

solutionbranch of the repository. To keep the course material maintainable, these only cover exercises where there is one obvious solution, not open-ended problems where you could go down many paths.

As in the CPU course, you can navigate between the course’s sections using several tools:

- The left-hand sidebar, which provides direct access to every page.

- If your browser window is thin, the sidebar may be hidden by default. In that case you can open (and later close) it using the top-left “triple dash” button.

- The left/right arrow buttons at the end of each page, or your keyboard’s arrow keys.

-

Problems linked to nonportable code include lack of future computation reproducibility, exploding hardware costs, reduced hardware innovation, and ecosystem fragility against unforeseen changes of politics like the ongoing race to the bottom in computational precision. ↩

Environment setup

The development environment for this course will largely extend that of the CPU course. You should therefore begin by following the environment setup process for the CPU course if you have not done so already, including the final test which makes sure that your Rust development environment does work as expected for CPU programming purposes.

Once this is done, we will proceed to extend this CPU development environment into a GPU development environment by going through the following steps:

- Try to make your GPU(s) available for Vulkan development. This is the hardest part, but if this step fails it’s not the end of the world, we can use a GPU emulator instead.

- Add Vulkan development tools to your Rust development environment.

- Download and unpack this course’s version of the

exercises/source code. - Test that the resulting setup is complete by running some of the course’s code examples.

Host GPU setup

Before a Vulkan-based program can use your GPU, a few system preparations are needed:

- Vulkan relies on GPU hardware features that were introduced around 2012. If your system’s GPUs are older than this, then you will almost certainly need to use a GPU emulator, and can ignore everything else that is said inside of this chapter.

- Doing any kind of work with a GPU requires a working GPU driver. Which, for some popular brands of GPUs, may unfortunately require some work.

- Doing Vulkan work specifically additionally requires a Vulkan implementation

that knows how to communicate with your GPU driver.

- Some GPU drivers provide their own Vulkan implementation. This is common on Windows, but also seen in e.g. NVidia’s Linux drivers.

- Other GPU drivers expose a standardized interface that a third-party Vulkan implementations can tap into. This is the norm on Linux on macOS.

It is important to point out that you will also need these preparations when using Linux containers, because the containers do not acquire full control of the GPU hardware. They need to go through the host system’s GPU driver, which must therefore be working.

In fact, as a word of warning, containerized setups will likely make it harder for you to get a working GPU setup.1 Given the option to do so, you should prefer using a native development environment for this course, or any other kind of coding that involves GPUs for that matter.

GPU driver

The procedure for getting a working GPU driver is, as you may imagine, fairly system-dependent. Please select your operating system using the tabs below:

macOS bundles suitable GPU drivers for all Apple-manufactured computers, and Macs should therefore require no extra GPU driver setup.2

After performing any setup step described above and rebooting, your system should have a working GPU driver. But owing to the highly system-specific nature of this step, we unfortunately won’t yet be able to check this in an OS-agnostic manner. To do that, we will install another component that you are likely to need for this course, namely a Vulkan implementation.

Vulkan implementation

As mentioned above, your GPU driver may or may not come with a Vulkan implementation. If that is not the case, we will want to install one.

Like Windows, macOS does not provide first-class Vulkan support out of the box because Apple want to push their own proprietary GPU API called Metal.

Unlike on Windows, however, there is no easy workaround based on installing the GPU manufacturer’s driver on macOS, because Apple is the manufacturer and unsurprisingly they do not provide an optional driver with Vulkan support either.

What we will therefore need to do is to layer a third-party Vulkan implementation on top of Apple’s proprietary Metal API. The MoltenVk project provides the most popular implementation of such a layered Vulkan implementation at the time of writing.

As the author sadly did not get the chance to experiment with a Mac during preparation of the course, we cannot provide precise installation instructions for MoltenVk. So please follow the installation instructions of the README file of the official code repository and ping the course author if you run into any trouble.

Update: During the 2025 edition of the school, the experience was that MoltenVk was reasonably easy to install and worked fine for the simple number-squaring GPU program that is presented in the first part of this course, but struggled building the full larger Gray-Scott simulation program. Help from expert macOS users in debugging this is welcome. If there are none in the audience, let us hope that someone else will encounter the issue and it will resolve itself in future MoltenVk releases…

Given this preparation, your system should now be ready to run Vulkan apps that use your GPU. How do we know for sure, however? A test app will come in handy here.

Final check

The best way to check if your Vulkan setup works is to run a Vulkan application that can display a list of available devices and make sure that your GPUs are featured in that list.

The Khronos Group, which maintains the Vulkan specification, provide a simple

tool for this in the form of the vulkaninfo app, which prints a list of all

available devices along with their properties. And for once, planets have

aligned properly and all package managers in common use have agreed to name the

package that contains this app identically. No matter if you use a Linux

distribution’s built-in package manager, brew for macOS, or vcpkg for

Windows, the package that contains this utility is called vulkan-tools on

every system that the author could think about.

There is just one problem: Vulkan devices have many properties, which means that

the default level of detail displayed by vulkaninfo is unbrearable. For

example, it emits more than 6000 lines of textual output on the author’s laptop

at the time of writing.

Thankfully there is an easy fix for that: add the --summary command line

option, and you will get a reasonably concise device list at the end of the

output. Here’s the output from the author’s laptop:

vulkaninfo --summary

[ ... global Vulkan implementation properties ... ]

Devices:

========

GPU0:

apiVersion = 1.4.311

driverVersion = 25.1.4

vendorID = 0x1002

deviceID = 0x1636

deviceType = PHYSICAL_DEVICE_TYPE_INTEGRATED_GPU

deviceName = AMD Radeon Graphics (RADV RENOIR)

driverID = DRIVER_ID_MESA_RADV

driverName = radv

driverInfo = Mesa 25.1.4-arch1.1

conformanceVersion = 1.4.0.0

deviceUUID = 00000000-0800-0000-0000-000000000000

driverUUID = 414d442d-4d45-5341-2d44-525600000000

GPU1:

apiVersion = 1.4.311

driverVersion = 25.1.4

vendorID = 0x1002

deviceID = 0x731f

deviceType = PHYSICAL_DEVICE_TYPE_DISCRETE_GPU

deviceName = AMD Radeon RX 5600M (RADV NAVI10)

driverID = DRIVER_ID_MESA_RADV

driverName = radv

driverInfo = Mesa 25.1.4-arch1.1

conformanceVersion = 1.4.0.0

deviceUUID = 00000000-0300-0000-0000-000000000000

driverUUID = 414d442d-4d45-5341-2d44-525600000000

GPU2:

apiVersion = 1.4.311

driverVersion = 25.1.4

vendorID = 0x10005

deviceID = 0x0000

deviceType = PHYSICAL_DEVICE_TYPE_CPU

deviceName = llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

driverID = DRIVER_ID_MESA_LLVMPIPE

driverName = llvmpipe

driverInfo = Mesa 25.1.4-arch1.1 (LLVM 20.1.6)

conformanceVersion = 1.3.1.1

deviceUUID = 6d657361-3235-2e31-2e34-2d6172636800

driverUUID = 6c6c766d-7069-7065-5555-494400000000

As you can see, this particular system has three Vulkan devices available:

- An AMD GPU that’s integrated into the same package as the CPU (low-power, low-performance)

- Another AMD GPU that is separated from the CPU aka discrete (high-power, high-performance)

- A GPU emulator called

llvmpipethat is useful for debugging, and as a fallback for systems where there is no easy way to get a real hardware GPU to work (e.g. continuous integration of software hosted on GitHub or GitLab).

If you see all the Vulkan devices that you expect in the output of this command, that’s great! You are done with this chapter and can move to the next one. Otherwise, please go through this page’s instructions slowly again, making sure that you have not forgotten anything, and if not ping the teacher and we’ll try to figure it out together.

-

In addition to a working GPU driver on the host sytem and a working Vulkan stack inside of the container, you need to have working communication between the two. This assumes that they are compatible, which is anything but a given when e.g. running Linux containers on Windows or macOS. It also doesn’t help that most container runtimes are designed to operate as a black box (with few ways for users to observe and control the inner machinery) and attempt to sandbox containers (which may prevent them from getting access to the host GPU in the default container runtime configuration). ↩

-

Unless you are using an exotic configuration like an old macOS release running on a recent computer, that is, but if you know how to get yourself into this sort of Apple-unsupported configuration, we trust you to also know how to keep its GPU driver working… :) ↩

-

NVidia’s GPU drivers have historically tapped into unstable APIs of the Linux kernel that may change across even bugfix kernel releases, and this makes them highly vulnerable to breakage across system updates. To make matters worse, their software license would also prevent Linux distributions from shipping these drivers into their official software repository, which prevented distributions from enforcing kernel/driver compatibility at the package manager level. The situation has recently improved for newer hardware (>= Turing generation), where a new “open-source driver” (actually a thin open-source layer over an enormous encrypted+signed binary blob running on a hidden RISC-V CPU because this is NVidia) has been released with a license that enables distributions to ship it as a normal package. ↩

-

The unfortunate popularity of “stable” distributions like Red Hat Enterprise or Ubuntu LTS, which take pride in embalming ancient software releases and wasting thousands of developer hours into backporting bugfixes from newer releases, make this harder than it should be. But when an old kernel gets in the way of hardware support and a full distribution upgrade is not an option, consider upgrading the kernel alone using facilities like Ubuntu’s “HardWare Enablement” (-hwe) kernel packages. ↩

Development tools

The Rust development environment that was set up for the CPU computing course contains many things that are also needed for this GPU computing course too. But we are also going to need a few other things that are specific to this course. To be more specific…

- If you previously used containers, you must first switch to

another container (based on the CPU one) that features Vulkan development

tools. Then you can adjust your container’s execution configuration to expose

host GPUs to the containerized Linux system.

- In the 2025 edition, it was reported that Windows and macOS container runtimes like Docker Desktop struggle with exposing GPU hardware from the host to the container. Users of these operating systems should either favor native installations or accept potentially getting stuck with a GPU emulation.

- If you previously performed a native installation, then you must install Vulkan development tools alongside the Rust development tools that you already have.

Linux containers

Switching to the new source code

As you may remember, when setting up your container for the CPU course, you

started by downloading and unpacking an archive which contains a source code

directory called exercises/.

We will do mostly the same for this course, but the source code will obviously

be different. Therefore, please rename your previous exercises directory to

something else (or switch to a different parent directory), then follow the

following instructions.

Provided that the curl and unzip utilities are installed, you can download

and unpack the source code in the current directory using the following sequence

of Unix commands:

if [ -e exercises ]; then

echo "ERROR: Please move or delete the existing 'exercises' subdirectory"

else

curl -LO https://numerical-rust-gpu-96deb7.pages.in2p3.fr/setup/exercises.zip \

&& unzip exercises.zip \

&& rm exercises.zip

fi

Switching to the GPU image

During the CPU course, you have used a container image with a name that has

numerical-rust-cpu in it, such as

gitlab-registry.in2p3.fr/grasland/numerical-rust-cpu/rust_light:latest. It is

now time to switch to another version of this image that has GPU tooling built

into it.

- If you used the image directly, that’s easy, just replace

cpuwithgpuin the image name and all associated container execution commands that you use. In the above example, you would switchgitlab-registry.in2p3.fr/grasland/numerical-rust-gpu/rust_light:latest. - If you built a container image of your own on top of the course’s image, then

you will have a bit more work to do, in the form of replaying your changes on

top of your new images. Which shouldn’t be too hard either… if you used a

proper

Dockerfileinstead of rawdocker commit.

But unfortunately, that’s not the end of it. Try to run vulkaninfo --summary

inside of the resulting container, and you will likely figure out that some of

your host GPUs are likely not visible inside of the container. If that’s the

case, then I have bad news for you: you have some system-specific work to do if

you want to be able to use your GPUs inside of the container.

Exposing host GPUs

Please click the following tab that best describes your host system for further guidance:

In the host setup section, we mentioned that NVidia’s Linux drivers use a monolithic design. Their GPU kernel driver and Vulkan implementation are packaged together in such a way that the Vulkan implementation is only guaranteed to work if paired with the exact GPU kernel driver from the same NVidia driver package version.

As it turns out, this design is not just unsatisfying from a software engineering best practices perspective. It also becomes an unending source of pain as soon as containers get involved.

A first problem is that NVidia’s GPU driver resides in the Linux kernel while the Vulkan driver is implemented as a user-space library. Whereas the whole idea of Linux containers is to keep the host’s kernel while replacing the userspace libraries and executables with those of a different Linux system. And unless the Linux distribution of the host and containerized systems are the same, the odds that they will use the exact same NVidia driver package version are low.

To work around this, many container runtimes provide an option called --gpus

(Docker, Podman) or --nv (Apptainer, Singularity) that lets you mount a bunch

of files from the user-space components of the NVidia driver of the host system.

This is pretty much the only way to get the NVidia GPU driver to work inside of a container, but it comes at a price: GPU programs inside of the container will be exposed to NVidia driver binaries that were not the ones that they were compiled and tested against, and which they may or may not be compatible with. In that sense, those container runtime options undermine the basic container promise of executing programs in a well-controlled environment.

To make matters worse, the NVidia driver package actually contains not just one, but two different Vulkan backends. One that is specialized towards X11 graphical environments, and another that works in Wayland and headless environment. As bad luck would have it, the backend selection logic gets confused by the hacks needed to get the NVidia driver to work inside of a Linux container, and wrongly selects the X11 backend. Which won’t work as this course’s containers do not have even a semblance of an X11 graphics rendering stack, because they don’t need one.

That second issue can be fixed by modifying an environment variable to override

the NVidia Vulkan implementation’s default backend selection logic and select

the right one. But that will come at the expense of losing support for every

other GPU on the system including the llvmpipe GPU emulator. As this is a

high-performance computing course, and NVidia GPUs tend to be more powerful than

any other GPU featured in the same system, we will consider this as an

acceptable tradeoff.

Putting it all together, adding the following command-line option to your

docker/podman/apptainer/singularity run commands should allow you to use your

host’s NVidia GPUs from inside the resulting container:

--gpus=all --env VK_ICD_FILENAMES=/usr/share/glvnd/egl_vendor.d/10_nvidia.json

New command line arguments and container image name aside, the procedure for starting up a container will be mostly identical to that used for the CPU course. So you will want to get back to the appropriate section of the CPU course’s container setup instructions and follow the instructions for your container and system configuration again.

Once that is done, please run vulkaninfo --summary inside of a shell within

the container and check that the Vulkan device list matches what you get on the host,

driver version details aside.

Testing your setup

Your Rust development environment should now be ready for this course’s practical work. I strongly advise testing it by running the following script:

curl -LO https://gitlab.in2p3.fr/grasland/numerical-rust-gpu/-/archive/solution/numerical-rust-gpu-solution.zip \

&& unzip numerical-rust-gpu-solution.zip \

&& rm numerical-rust-gpu-solution.zip \

&& cd numerical-rust-gpu-solution/exercises \

&& echo "------" \

&& cargo run --release --bin info -- -p \

&& echo "------" \

&& cargo run --release --bin square -- -p \

&& cd ../.. \

&& rm -rf numerical-rust-gpu-solution

It performs the following actions, whose outcome should be manually checked:

- Run a Rust program that should produce the same device list as

vulkaninfo --summary. This tells you that any device that gets correctly detected by a C Vulkan program also gets correctly detected by a Rust Vulkan program, as one would expect. - Run another program that uses a simple heuristic to pick the Vulkan device that should be most performant, then uses that device to square an array of floating-point numbers, then checks the results. You should make sure the device selection that this program made is sensible and its final result check passed.

- If everything went well, the script will clean up after itself by deleting all previously created files.

Native installation

While containers are often lauded for making it easier to reproduce someone else’s development environment on your machine, GPUs actually invert this rule of thumb. As soon GPUs get involved, it’s often easier to get something working with a native installation.

The reason why that is the case is that before we get any chance of having a working GPU setup inside of a container, we must first get a working GPU setup on the host system. And once you have taken care of that (which is often the hardest part), getting the rest of a native development environment up and running is not that much extra work.

As before, we will will assume that you have already taken care of setting up a native development environment for Rust CPU development, and this documentation will therefore only focus on the changes needed to get this setup ready for native Vulkan development. Which will basically boil down to installing a couple of Vulkan development tools.

Vulkan validation layers

Vulkan came in a context where GPU applications were often bottlenecked by API overheads, and one of its central design goals was to improve upon that. A particularly controversial decision taken then was to remove mandatory parameter validation from the API, instead making it undefined behavior to pass any kind of unexpected parameter value to a Vulkan function.

This may be amazing for run-time performance, but certainly does not result in a great application development experience. Therefore it was also made possible to bring such checks back as an optional “validation” layer, that is meant to be used during application development and later removed in production. As a bonus, because this layer was only meant for development purposes and operated under no performance constraint, it could also…

- Perform checks that are much more detailed than those that any GPU API performed before, finding more errors in GPU-side code and CPU-GPU synchronization patterns.

- Supplement API usage error reporting with more opinionated “best practices” and “performance” lints that are more similar to compiler warnings in spirit.

Because this package is meant to be used for development purposes, it is not a default part of Vulkan installations. Thankfully, all commonly used systems have a package for that:

- Debian/Ubuntu/openSUSE/Brew:

vulkan-validationlayers - Arch/Fedora/RHEL:

vulkan-validation-layers - Windows: Best installed as part of the LunarG Vulkan SDK

shaderc

Older GPU APIs relied on GPU drivers to implement a compiler for a C-like language, which proved to be a bad idea as GPU manufacturers are terrible compiler developers (and terrible software developers in general). Applications thus experienced constant issues linked to those compilers, from uneven performance across hardware to incorrect run-time program behavior.

To get rid of this pain, Vulkan has switched to an AoT/JiT hybrid compilation model where GPU code is first compiled into a simplified assembly-like interpreted representation called SPIR-V on the developer’s machine, and it is this intermediate representation that gets sent to the GPU driver for final compilation into a device- and driver-specific binary.

Because of this, our development setup is going to require a compiler that goes

from the GLSL domain-specific language (which is a common choice for GPU code,

we’ll get into why during the course) to SPIR-V. The vulkano Rust binding that

we use is specifically designed to use

shaderc, which is a compiler that is

maintained by the Android development team.

Unfortunately, shaderc is not packaged by all Linux distributions. You may

therefore need to either use the official

binaries or

build it from source. In the latter case, you are going to need…

- CMake

- Ninja

- C and C++ compilers

- Python

- git

…and once those dependencies are available, you should be able to build and

install the latest upstream-tested version of shaderc and its dependencies

using the following script:

git clone --branch=known-good https://github.com/google/shaderc \

&& cd shaderc \

&& ./update_shaderc_sources.py \

&& cd src \

&& ./utils/git-sync-deps \

&& mkdir build \

&& cd build \

&& cmake -GNinja -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release .. \

&& ninja \

&& ctest -j$(nproc) \

&& sudo ninja install \

&& cd ../../.. \

&& rm -rf shaderc

Whether you download binaries or build from source, the resulting shaderc

installation location will likely not be in the default search path of the

associated shaderc-sys Rust bindings. We will want to fix this, otherwise the

bindings will try to be helpful by automatically downloading and building an

internal copy of shaderc insternally. This may fail if the dependencies are

not available, and is otherwise inefficient as such a build will need to be

performed once per project that uses shaderc-sys and again if the build

directory is ever discarded using something like cargo clean.

To point shaderc-sys in the right direction, find the directory in which the

libshaderc_combined static library was installed (typically some variation of

/usr/local/lib when building from source on Unix systems). Then adjust your

Rust development environment’s configuration so that the SHADERC_LIB_DIR

environment variable is set to point to this directory.

Syntax highlighting

For an optimal GPU development experience, you will want to set up your code

editor to apply GLSL syntax highlighting to files with a .comp extension. In

the case of Visual Studio Code, this can be done by installing the

slevesque.shader extension.

Testing your setup

Your Rust development environment should now be ready for this course’s practical work. I strongly advise testing it by running the following script:

curl -LO https://gitlab.in2p3.fr/grasland/numerical-rust-gpu/-/archive/solution/numerical-rust-gpu-solution.zip \

&& unzip numerical-rust-gpu-solution.zip \

&& rm numerical-rust-gpu-solution.zip \

&& cd numerical-rust-gpu-solution/exercises \

&& echo "------" \

&& cargo run --release --bin info -- -p \

&& echo "------" \

&& cargo run --release --bin square -- -p \

&& cd ../.. \

&& rm -rf numerical-rust-gpu-solution

It performs the following actions, whose outcome should be manually checked:

- Run a Rust program that should produce the same device list as

vulkaninfo --summary. This tells you that any device that gets correctly detected by a C Vulkan program also gets correctly detected by a Rust Vulkan program, as one would expect. - Run another program that uses a simple heuristic to pick the Vulkan device that should be most performant, then uses that device to square an array of floating-point numbers, then checks the results. You should make sure the device selection that this program made is sensible and its final result check passed.

- If everything went well, the script will clean up after itself by deleting all previously created files.

Training-day instructions

Expectations and conventions

Welcome to this practical about high-performance GPU computing in Rust!

This course is meant to follow the previous one, which is about CPU computing. It is assumed that you have followed that course, and therefore we will not repeat anything that was said there. However, if your memory is hazy and you are unsure about what a particular construct in the Rust code examples does, please ping the teacher for guidance.

Although some familiarity with Rust CPU programming is assumed, no particular GPU programming knowledge is expected beyond basic knowledge of GPU hardware architecture. Indeed, the GPU API that we will use (Vulkan) is different enough from other (CUDA- or OpenMP-like) APIs that are more commonly used in HPC that knowledge of those APIs may cause extra confusion. The course’s introduction explains why we are using Vulkan and not these other APIs like everyone else.

Exercises source code

At the time where you registered, you should have been directed to instructions for setting up your development environment. If you did not follow these instructions yet, this is the right time!

Now that the course has begun, we will download a up-to-date copy of the

exercises’ source code and unpack it somewhere inside of your

development environement. This will create a subdirectory called exercises/ in

which we will be working during the rest of the course.

Please pick your environement below in order to get appropriate instructions:

From a shell inside of the container1, run the following sequence of commands to update the exercises source code that you have already downloaded during container setup.

Beware that any change to the previously downloaded code will be lost in the process.

cd ~

# Can't use rm -rf exercises because we must keep the bind mount alive

for f in $(ls -A exercises); do rm -rf exercises/$f; done \

&& curl -LO https://numerical-rust-gpu-96deb7.pages.in2p3.fr/setup/exercises.zip \

&& unzip -u exercises.zip \

&& rm exercises.zip \

&& cd exercises

General advice

Some exercises are based on code examples that are purposely incorrect. Therefore, if some code fails to build, it may not come from a mistake of the course author, but from some missing work on your side. The course material should explicitly point out when that is the case.

If you encounter any failure which does not seem expected, or if you otherwise get stuck, please call the trainer for guidance!

With that being said, let’s get started with actual Rust code. You can move to the next page, or any other page within the course for that matter, through the following means:

- Left and right keyboard arrow keys will switch to the previous/next page. Equivalently, arrow buttons will be displayed at the end of each page, doing the same thing.

- There is a menu on the left (not shown by default on small screen, use the top-left button to show it) that allows you to quickly jump to any page of the course. Note, however, that the course material is designed to be read in order.

- With the magnifying glass icon in the top-left corner, or the “S” keyboard shortcut, you can open a search bar that lets you look up content by keywords.

-

If you’re using

rust_code_server, this means using the terminal pane of the web-based VSCode editor. ↩ -

That would be a regular shell for a local Linux/macOS installation and a Windows Subsystem for Linux shell for WSL. ↩

Instance

Any API that lets developers interact with a complex system must strike a balance between flexibility and ease of use. Vulkan goes unusually far on the flexibility side of this tradeoff by providing you with many tuning knobs at every stage of an execution process that most other GPU APIs largely hide from you. It therefore requires you to acquire an unusually good understanding of the complex process through which a GPU-based program gets things done.

In the first part of this course, we will make this complexity tractable by introducing it piece-wise, in the context of a trivial GPU program that merely squares an array of floating-point numbers. In the second part of the course, you will then see that once these basic concepts of Vulkan are understood, they easily scale them up to the complexity of a full Gray-Scott reaction.

As a first step, this chapter will cover how you can load the Vulkan library from Rust, set up a Vulkan instance in a way that eases later debugging, and enumerate available Vulkan devices.

Introducing vulkano

The first step that we must take before we can use Vulkan in Rust code, is to link your program to a Vulkan binding. This is a Rust crate that handles the hard work of linking to the Vulkan C library and exposing a Rust layer on top of it so that your Rust code may interact with it.

In this course, we will use the vulkano crate for this

purpose. This crate builds on top of the auto-generated

ash crate, which closely matches the Vulkan

C API with only minor Rust-specific API tweaks, by supplementing it with two

layers of abstraction:

- A low-level layer that re-exposes Vulkan types and functions in a manner that is more in line with Rust programmer expectations. For example, C-style free functions that operate on their first pointer parameter are replaced with Rust-style structs with methods.

- A high-level layer that automates away some common operations (like sub-allocation of GPU memory allocations into smaller chunks) and makes as many operations as possible safe (no possibility for undefined behavior).

Crucially, this layering is fine-grained (done individually for each Vulkan object type) and transparent (any high-level object lets you access the lower-level object below it). As a result, if you ever encounter a situation where the high-level layer has made design choices that are not right for your use case, you are always able to drop down to a lower-level layer and do things your own way.

This means that anything you can do with raw Vulkan API calls, you can also do

with vulkano. But vulkano will usually give you an alternate way to do

things that is easier, fast/flexible enough for most purposes, and requires a

lot less unsafe Rust code that must be carefully audited for memory/thread/type

safety. For many applications, this is a better tradeoff than using ash

directly.

The vulkano dependency has already been added to this course’s example code,

but for reference, this is how you would add it:

# You do not need to type in this command, it has already been done for you

cargo add --no-default-features --features=macros vulkano

This adds the vulkano dependency in a manner that disables the x11 feature

that enables X11 support. This feature is not needed for this course, where we

are not rendering images to X11 windows. And it won’t work in this course’s

Linux containers, which do not contain a complete X11 stack as this would

unnecessarily increase download size.

We do, however, keep the macros features on, because we will need it in order

to use the vulkano-shaders crate later on. We’ll discuss what this crate

does and why we need it in a future chapter.

Loading the library

Now that we have the vulkano binding available, we can use it to load the

Vulkan library. In principle, you could customize this loading process to e.g.

switch between different Vulkan libraries, but in practice this is rarely needed

because as we will see later Vulkan provides several tools to customize the

behavior of the library.

Hence, for the purpose of this course, we will stick with the default

vulkano library-loading method, which is appropriate for almost every Vulkan

application:

use std::error::Error;

use vulkano::library::VulkanLibrary;

// Simplify error handling with type-erased errors

type Result<T> = std::result::Result<T, Box<dyn Error>>;

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Load the Vulkan library

let library = VulkanLibrary::new()?;

// ...

Ok(())

}Like all system operations, loading the library can fail if e.g. no Vulkan implementation is installed on the host system, and we need to handle that.

Here, we choose to do it the easy way by converting the associated error type

into a type-erased Box<dyn Error> type that can hold all error types, and

bubbling this error out of the main() function using the ? error propagation

operator. The Rust runtime will then take care of displaying the error message

and aborting the program with a nonzero exit code. This basic error handling

strategy is good enough for the simple utilities that we will be building

throughout this course.

Once errors are handled, we may query the resulting VulkanLibrary object.

For example, we can…

- Check which revision of the Vulkan specification is supported. This versioning allows the Vulkan specification to evolve by telling us which newer features can be used by our application.

- Check which Vulkan extensions are supported. Extensions allow Vulkan to support features that do not make sense on every single system supported by the API, such as the ability to display visuals in X11 and Wayland windows on Linux.

- Check which Vulkan layers are available. Layers are stackable plugins that customize

the behavior of your Vulkan library without replacing it. For example,

the popular

VK_LAYER_KHRONOS_validationlayer adds error checking to all Vulkan functions, allowing you to check your application’s debug builds without slowing down its release builds.

Once we have learned what we need to know, we can then proceed with the next setup step, which is to set up a Vulkan API instance.

Setting up an instance

An Vulkan Instance is configured from a VulkanLibrary by specifying a

few things about our application, including which optional Vulkan library

features we want to use.

For reasons that will soon become clear, we must set up an Instance before

we can do anything else with the Vulkan API, including enumerating available

devices.

While the basic process is easy, we will take a few detours along the way to set up some optional Vulkan features that will make our debugging experience nicer later on.

vulkano configuration primer

For most configuration work, vulkano uses a recuring API design pattern that

is based on configuration structs, where most fields have a default value.

When combined with Rust’s functional struct update syntax, this API design allows you to elegantly specify only the parameters that you care about. Here is an example:

use vulkano::instance::{InstanceCreateInfo, InstanceCreateFlags};

let instance_info = InstanceCreateInfo {

flags: InstanceCreateFlags::ENUMERATE_PORTABILITY,

..InstanceCreateInfo::application_from_cargo_toml()

};The above instance configuration struct expresses the following intent:

- We let the Vulkan implementation expose devices that do not fully conform with the Vulkan specification, but only a slightly less featureful “portability subset” thereof. This is needed for some exotic Vulkan implementations like MoltenVk, which layers on top of macOS’ Metal API to work around Apple’s lack of Vulkan support.

- We let

vulkanoinfer the application name and version from our Cargo project’s metadata, so that we do not need to specify the same information in two different places. - For all other fields of the

InstanceCreateInfostruct, we use the default instance configuration, which is to provide no extra information about our app to the Vulkan implementation and to enable no optional features.

Most optional Vulkan instance features are about interfacing with your operating system’s display features for rendering visuals on screen and are not useful for the kind of headless computations that we are going to study in this course. However, there are two optional Vulkan debugging features that we strongly advise enabling on every platform that supports them:

- If the

VK_LAYER_KHRONOS_validationlayer is available, then it is a good idea to enable it in your debug builds. This enables debugging features falling in the following categories, at a runtime performance cost:- Error checking for Vulkan entry points, whose invalid usage normally results

in instant Undefined Behavior.

vulkano’s high level layer is already meant to prevent or report such incorrect usage, but unfortunately it is not immune to the occasional bug or limitation. It is thus good to have some defense-in-depth against UB in your debug builds before you try to report a GPU driver bug that later turns out to be avulkanobug. - “Best practices” linting which detects suspicious API usage that is not illegal per the spec but may e.g. cause performance issues. This is basically a code linter executing at run-time with full knowledge of the application state.

- Ability to use

printf()in GPU code in order to easily investigate its state when it behaves unexpectedly, aka “Debug Printf”.

- Error checking for Vulkan entry points, whose invalid usage normally results

in instant Undefined Behavior.

- The

VK_EXT_debug_utilsextension lets you send diagnostic messages from the Vulkan implementation to your favorite log output (stderr,syslog…). I would advise enabling it for both debug and release builds, on all systems that support it.- In addition to being heavily used by the aforementioned validation layer, these messages often provide invaluable context when you are trying to diagnose why an application refuses to run as expected on someone else’s computer.

Indeed, these two debugging features are so important that vulkano provides

dedicated tooling for enabling and configuring them. Let’s look into that.

Validation layer

As mentioned above, the Vulkan validation layer has some runtime overhead and

partially duplicates the functionality of vulkano’s safe API. Therefore, it is

normally only enabled in in debug builds.

We can check if the program is built in debug mode using the

cfg!(debug_assertions) expression. When that is the case, we will want to

check if the VK_LAYER_KHRONOS_validation layer is available, and if so add it

to the set of layers that we enable for our instance:

// Set up a blank instance configuration.

//

// For what we are going to do here, an imperative style will be more effective

// than the functional style shown above, which is otherwise preferred.

let mut instance_info = InstanceCreateInfo::application_from_cargo_toml();

// In debug builds...

if cfg!(debug_assertions)

// ...if the validation layer is available...

&& library.layer_properties()?

.any(|layer| layer.name() == "VK_LAYER_KHRONOS_validation")

{

// ...then enable it...

instance_info

.enabled_layers

.push("VK_LAYER_KHRONOS_validation".into());

// TODO: ...and configure it

}

// TODO: Proceed with rest of instance configurationBack in the Vulkan 1.0 days, simply enabling the layer like this would have been enough. But as the TODO above suggests, the validation layer have since acquired optional features which are not enabled by default, largely because of their performance impact.

Because we only enable the validation layer in debug builds, where runtime

performance is not a big concern, we can enable as many of those as we like by

pushing the appropriate

flags

into the

enabled_validation_features

member of our InstanceCreateInfo struct. The only limitation that we must

respect in doing so is that GPU-assisted validation (which provides extended

error checking) is incompatible with use of printf() in GPU code. For the

purpose of this course, we will priorize GPU-assisted validation over GPU

printf().

The availability of these fine-grained settings is signaled by support of the

VK_EXT_validation_features

layer extension.1 We can detect this extension and enable it along with

almost every feature except for GPU printf() using the following code:

use vulkano::instance::debug::ValidationFeatureEnable;

if library

.supported_layer_extensions("VK_LAYER_KHRONOS_validation")?

.ext_validation_features

{

instance_info.enabled_extensions.ext_validation_features = true;

instance_info.enabled_validation_features.extend([

ValidationFeatureEnable::GpuAssisted,

ValidationFeatureEnable::GpuAssistedReserveBindingSlot,

ValidationFeatureEnable::BestPractices,

ValidationFeatureEnable::SynchronizationValidation,

]);

}And if we put it all together, we get the following validation layer setup routine:

/// Enable Vulkan validation layer in debug builds

fn enable_debug_validation(

library: &VulkanLibrary,

instance_info: &mut InstanceCreateInfo,

) -> Result<()> {

// In debug builds...

if cfg!(debug_assertions)

// ...if the validation layer is available...

&& library.layer_properties()?

.any(|layer| layer.name() == "VK_LAYER_KHRONOS_validation")

{

// ...then enable it...

instance_info

.enabled_layers

.push("VK_LAYER_KHRONOS_validation".into());

// ...along with most available optional features

if library

.supported_layer_extensions("VK_LAYER_KHRONOS_validation")?

.ext_validation_features

{

instance_info.enabled_extensions.ext_validation_features = true;

instance_info.enabled_validation_features.extend([

ValidationFeatureEnable::GpuAssisted,

ValidationFeatureEnable::GpuAssistedReserveBindingSlot,

ValidationFeatureEnable::BestPractices,

ValidationFeatureEnable::SynchronizationValidation,

]);

}

}

Ok(())

}To conclude this section, it should be mentioned that the Vulkan validation

layer is not featured in the default Vulkan setup of most Linux distributions,

and must often be installed separately. For example, on Ubuntu, the

vulkan-validationlayers separate package must be installed first. This is one

reason why you should never force-enable validation layers in production Vulkan

binaries.

Logging configuration

Now that validation layer has been taken care of, let us turn our attention to the other optional Vulkan debugging feature that we highlighted as worth enabling whenever possible, namely logging of messages from the Vulkan implementation.

Vulkan logging is configured using the

DebugUtilsMessengerCreateInfo

struct. There are three main things that we must specify here:

- What message severities

we want to handle.

- As in most logging systems, a simple

ERROR/WARNING/INFO/VERBOSEclassification is used. But in Vulkan, enabling a certain severity does not implicitly enable higher severities, so you can e.g. handleERRORandVERBOSEmessages using different strategies without handlingWARNINGandINFOmessages at all. - In typical Vulkan implementations,

ERRORandWARNINGmessages should be an exceptional event, whereasINFOandVERBOSEmessages can be sent at an unpleasantly high frequency. However anERROR/WARNINGmessage is often only understandable given the context of previousINFO/VERBOSEmessages. It is therefore a good idea to printERRORandWARNINGmessages by default, but provide an easy way to printINFO/VERBOSEmessages too when needed.

- As in most logging systems, a simple

- What message

types we want to handle.

- Most Vulkan implementation messages will fall in the

GENERALcategory, but the validation layer may send messages in theVALIDATIONandPERFORMANCEcategory too. As you may guess, the latter messages types report application correctness and runtime performance issues respectively.

- Most Vulkan implementation messages will fall in the

- What we want to

do

when a message matches the above criteria.

- Building such a

DebugUtilsMessengerCallbackisunsafebecausevulkanocannot check that your messaging callback, which is triggered by Vulkan API calls, does not make any Vulkan API calls itself. Doing so is forbidden for hopefully obvious reasons.2 - Because we are building simple programs here, where the complexity of a

production-grade logging system like

syslogis unnecessary, we will simply forward these messages tostderr. For our first Vulkan program, aneprintln!()call will suffice. - Vulkan actually uses a form of structured logging, where the logging callback does not receive just a message string, but also a bunch of associated metadata about the context in which the message was emitted. In the interest of simplicity, our callback will only print out a subset of this metadata, which should be enough for our purposes.

- Building such a

As mentioned above, we should expose the message severity tradeoff to the user.

We can do this using a simple clap CLI interface.

Here we will leverage clap’s Args feature, which lets us modularize our CLI

arguments into several independent structs. This will later allow us to build

multiple clap-based programs that share some common command-line arguments.

Along the way, we will also expose the ability discussed in the beginning of

this chapter to probe devices which are not fully Vulkan-compliant.

use clap::Args;

/// Vulkan instance configuration

#[derive(Debug, Args)]

pub struct InstanceOptions {

/// Increase Vulkan log verbosity. Can be specified multiple times.

#[arg(short, long, action = clap::ArgAction::Count)]

pub verbose: u8,

}Once we have that, we can set up some basic Vulkan logging configuration…

use vulkano::instance::debug::{

DebugUtilsMessageSeverity, DebugUtilsMessageType,

DebugUtilsMessengerCallback, DebugUtilsMessengerCreateInfo

};

/// Generate a Vulkan logging configuration

fn logger_info(options: &InstanceOptions) -> DebugUtilsMessengerCreateInfo {

// Select accepted message severities

type S = DebugUtilsMessageSeverity;

let mut message_severity = S::ERROR | S::WARNING;

if options.verbose >= 1 {

message_severity |= S::INFO;

}

if options.verbose >= 2 {

message_severity |= S::VERBOSE;

}

// Accept all message types

type T = DebugUtilsMessageType;

let message_type = T::GENERAL | T::VALIDATION | T::PERFORMANCE;

// Define the callback that turns messages to logs on stderr

// SAFETY: The logging callback makes no Vulkan API call

let user_callback = unsafe {

DebugUtilsMessengerCallback::new(|severity, ty, data| {

// Format message identifiers, if any

let id_name = if let Some(id_name) = data.message_id_name {

format!(" {id_name}")

} else {

String::new()

};

let id_number = if data.message_id_number != 0 {

format!(" #{}", data.message_id_number)

} else {

String::new()

};

// Put most information into a single stderr output

eprintln!("[{severity:?} {ty:?}{id_name}{id_number}] {}", data.message);

})

};

// Put it all together

DebugUtilsMessengerCreateInfo {

message_severity,

message_type,

..DebugUtilsMessengerCreateInfo::user_callback(user_callback)

}

}Instance and logger creation

Now that we have a logger configuration, we are almost ready to enable logging. There are just two remaining concerns to take care of:

- Logging uses the optional Vulkan

VK_EXT_debug_utilsextension that may not always be available. We must check for its presence and enable it if available. - For mysterious reasons, Vulkan allows programs to use different logging

configurations at the time where an

Instanceis being set up and afterwards. This means that we will need to set up logging twice, once at the time where we create anInstanceand another time after that.

After instance creation, logging is taken care of by a separate

DebugUtilsMessenger

object, which follows the usual RAII design: as long as it is alive, messages

are logged, and once it is dropped, logging stop. If you want logging to happen

for an application’s entire lifetime (which you usually do), the easiest way to

avoid dropping this object too early is to bundle it with your other long-lived

Vulkan objects in a long-lived “context” struct.

We will now demonstrate this pattern with a struct that combines a Vulkan instance with optional logging. Its constructor sets up all aforementioned features, including logging if available:

use std::sync::Arc;

use vulkano::instance::{

debug::DebugUtilsMessenger, Instance, InstanceCreateFlags

};

/// Vulkan instance, with associated logging if available

pub struct LoggingInstance {

pub instance: Arc<Instance>,

pub messenger: Option<DebugUtilsMessenger>,

}

//

impl LoggingInstance {

/// Set up a `LoggingInstance`

pub fn new(library: Arc<VulkanLibrary>, options: &InstanceOptions) -> Result<Self> {

// Prepare some basic instance configuration from Cargo metadata, and

// enable portability subset device for macOS/MoltenVk compatibility

let mut instance_info = InstanceCreateInfo {

flags: InstanceCreateFlags::ENUMERATE_PORTABILITY,

..InstanceCreateInfo::application_from_cargo_toml()

};

// Enable validation layers in debug builds

enable_debug_validation(&library, &mut instance_info)?;

// Set up logging to stderr if the Vulkan implementation supports it

let mut log_info = None;

if library.supported_extensions().ext_debug_utils {

instance_info.enabled_extensions.ext_debug_utils = true;

let config = logger_info(options);

instance_info.debug_utils_messengers.push(config.clone());

log_info = Some(config);

}

// Set up instance, logging creation-time messages

let instance = Instance::new(library, instance_info)?;

// Keep logging after instance creation

let instance2 = instance.clone();

let messenger = log_info

.map(move |config| DebugUtilsMessenger::new(instance2, config))

.transpose()?;

Ok(LoggingInstance {

instance,

messenger,

})

}

}…and once we have that, we can query this instance to enumerate available devices on the system, for the purpose of picking (at least) one that we will eventually run computations on. This will be the topic of the next exercise, and the next chapter after that.

Exercise

Introducing info

The exercises/ codebase that you have been provided with contains a set of

executable programs (in src/bin), that share some code via a common utility

library (at the root of src/). Most of the code introduced in this chapter is

located in the instance module of this utility library.

The info executable, whose source code lies in src/bin/info.rs, lets you

query some properties of your system’s Vulkan setup. You can think of it as a

simplified version of the classic vulkaninfo utility from the Linux

vulkan-tools package, with a less overwhelming default configuration.

You can run this executable using the following Cargo command…

cargo run --bin info

…and if your Vulkan implementation is recent enough, you may notice that the validation layer is already doing its job by displaying some warnings:

Click here for example output

[WARNING VALIDATION VALIDATION-SETTINGS #2132353751] vkCreateInstance(): Both GPU Assisted Validation and Normal Core Check Validation are enabled, this is not recommend as it will be very slow. Once all errors in Core Check are solved, please disable, then only use GPU-AV for best performance.

[WARNING VALIDATION BestPractices-specialuse-extension #1734198062] vkCreateInstance(): Attempting to enable extension VK_EXT_debug_utils, but this extension is intended to support use by applications when debugging and it is strongly recommended that it be otherwise avoided.

[WARNING VALIDATION BestPractices-deprecated-extension #-628989766] vkCreateInstance(): Attempting to enable deprecated extension VK_EXT_validation_features, but this extension has been deprecated by VK_EXT_layer_settings.

[WARNING VALIDATION BestPractices-specialuse-extension #1734198062] vkCreateInstance(): Attempting to enable extension VK_EXT_validation_features, but this extension is intended to support use by applications when debugging and it is strongly recommended that it be otherwise avoided.

Vulkan instance ready:

- Max API version: 1.3.281

- Physical devices:

[WARNING VALIDATION WARNING-GPU-Assisted-Validation #615892639] vkGetPhysicalDeviceProperties2(): Internal Warning: Setting VkPhysicalDeviceVulkan12Properties::maxUpdateAfterBindDescriptorsInAllPools to 32

[WARNING VALIDATION WARNING-GPU-Assisted-Validation #615892639] vkGetPhysicalDeviceProperties2(): Internal Warning: Setting VkPhysicalDeviceVulkan12Properties::maxUpdateAfterBindDescriptorsInAllPools to 32

0. AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

* Device type: DiscreteGpu

1. llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

* Device type: Cpu

Thankfully, these warnings are mostly inconsequential:

- The

VALIDATION-SETTINGSwarning complains that we are using an unnecessarily exhaustive validation configuration, which can have a strong averse effect on runtime performance. It suggests running the program multiple times with less extensive validation. This is cumbersome, though, which is why in this course we just let debug builds be slow. - The

BestPractices-specialuse-extensionwarnings complain about our use of debugging-focused extensions. But we do it on purpose to make debugging easier. - The

BestPractices-deprecated-extensionwarning complains about a genuine issue (we are using an old extension to configure the validation layer), however we can’t easily fix this issue right now (vulkanodoes not support the new configuration mechanism yet). - The

WARNING-GPU-Assisted-Validationwarnings complain about an internal implementation detail of GPU-assisted validation that we have no control on. It suggests a possible bug in GPU-assisted validation that should be reported at some point.

Other operating modes

By running a release build of the program instead, we see that the warnings go away, highlighting the fact that validation layers are only enabled in debug builds:

cargo run --release --bin info

Click here for example output

Vulkan instance ready:

- Max API version: 1.3.281

- Physical devices:

0. AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

* Device type: DiscreteGpu

1. llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

* Device type: Cpu

…however, if you increase the Vulkan log verbosity by specifying the -v

command-line option to the output binary (which goes after a -- to separate it

from Cargo options), you will see that Vulkan logging remains enabled even in

release builds, as we would expect.

cargo run --release --bin info -- -v

Click here for example output

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] No valid vk_loader_settings.json file found, no loader settings will be active

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Searching for implicit layer manifest files

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] In following locations:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.config/vulkan/implicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.config/kdedefaults/vulkan/implicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /etc/xdg/vulkan/implicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /etc/vulkan/implicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.local/share/vulkan/implicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.local/share/flatpak/exports/share/vulkan/implicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /var/lib/flatpak/exports/share/vulkan/implicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/local/share/vulkan/implicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/implicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found the following files:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /etc/vulkan/implicit_layer.d/renderdoc_capture.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/implicit_layer.d/MangoHud.x86_64.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/implicit_layer.d/VkLayer_MESA_device_select.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /etc/vulkan/implicit_layer.d/renderdoc_capture.json (file version 1.1.2)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/implicit_layer.d/MangoHud.x86_64.json (file version 1.0.0)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/implicit_layer.d/VkLayer_MESA_device_select.json (file version 1.0.0)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Searching for explicit layer manifest files

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] In following locations:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.config/vulkan/explicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.config/kdedefaults/vulkan/explicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /etc/xdg/vulkan/explicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /etc/vulkan/explicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.local/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.local/share/flatpak/exports/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /var/lib/flatpak/exports/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/local/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found the following files:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_api_dump.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_monitor.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_screenshot.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_khronos_validation.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_INTEL_nullhw.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_MESA_overlay.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_MESA_screenshot.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_MESA_vram_report_limit.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_api_dump.json (file version 1.2.0)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_monitor.json (file version 1.0.0)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_screenshot.json (file version 1.2.0)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_khronos_validation.json (file version 1.2.0)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_INTEL_nullhw.json (file version 1.0.0)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_MESA_overlay.json (file version 1.0.0)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_MESA_screenshot.json (file version 1.0.0)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/explicit_layer.d/VkLayer_MESA_vram_report_limit.json (file version 1.0.0)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Searching for driver manifest files

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] In following locations:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.config/vulkan/icd.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.config/kdedefaults/vulkan/icd.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /etc/xdg/vulkan/icd.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /etc/vulkan/icd.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.local/share/vulkan/icd.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /home/hadrien/.local/share/flatpak/exports/share/vulkan/icd.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /var/lib/flatpak/exports/share/vulkan/icd.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/local/share/vulkan/icd.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/icd.d

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found the following files:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/icd.d/radeon_icd.x86_64.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] /usr/share/vulkan/icd.d/lvp_icd.x86_64.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found ICD manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/icd.d/radeon_icd.x86_64.json, version 1.0.0

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Found ICD manifest file /usr/share/vulkan/icd.d/lvp_icd.x86_64.json, version 1.0.0

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Insert instance layer "VK_LAYER_MESA_device_select" (libVkLayer_MESA_device_select.so)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] vkCreateInstance layer callstack setup to:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] <Application>

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] ||

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] <Loader>

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] ||

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] VK_LAYER_MESA_device_select

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Type: Implicit

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Enabled By: Implicit Layer

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Disable Env Var: NODEVICE_SELECT

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Manifest: /usr/share/vulkan/implicit_layer.d/VkLayer_MESA_device_select.json

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Library: libVkLayer_MESA_device_select.so

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] ||

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] <Drivers>

Vulkan instance ready:

- Max API version: 1.3.281

- Physical devices:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] linux_read_sorted_physical_devices:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Original order:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [0] llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [1] AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Sorted order:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [0] AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [1] llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] linux_read_sorted_physical_devices:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Original order:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [0] llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [1] AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Sorted order:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [0] AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [1] llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] linux_read_sorted_physical_devices:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Original order:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [0] llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [1] AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Sorted order:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [0] AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [1] llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] linux_read_sorted_physical_devices:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Original order:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [0] llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [1] AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] Sorted order:

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [0] AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

[INFO GENERAL Loader Message] [1] llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

0. AMD Radeon Pro WX 3200 Series (RADV POLARIS12)

* Device type: DiscreteGpu

1. llvmpipe (LLVM 20.1.6, 256 bits)

* Device type: Cpu

Hands-on

You can query the full list of available command-line flags using the standard

--help command option, which goes after -- like other non-Cargo options.

Please play around with the various available CLI options and try to use this

utility to answer the following questions:

- Is your computer’s GPU correctly detected, or do you only see a

llvmpipeCPU emulation device (or worse, no device at all) ?- Please report absence of a GPU device to the teacher, with a bit of luck we may find the right system configuration tweak to get it to work.

- What optional instance extensions and layers does your Vulkan implementation support?

- How much device-local memory do your GPUs have ?

- What Vulkan extensions do your GPUs support ?

- (Linux-specific) Can you tell where on disk the shared libraries featuring Vulkan drivers (known as Installable Client Drivers or ICDs in Khronos API jargon) are stored ?

Once your thirst for system configuration knowledge is quenched, you may then study the source code of this program. Which is admittedly not the prettiest as it priorizes beginner readability over maximal maintainability in more than one place…

Overall, this program demonstrates how various system properties can be queried

using the VulkanLibrary and Instance APIs. But not all available

properties are exposed because the Vulkan specification is huge and we are only

going to cover a subset of it in this course. However, if any property in the

documentation linked above gets you curious, do not hesitate to adjust the code

of the info program so that it gets printed as well!

-

…which has recently been deprecated and scheduled for replacement by

VK_EXT_layer_settings, but alasvulkanodoes not support this new layer configuration mechanism yet. ↩ -

The Vulkan messaging API allows for synchronous implementations. In such implementations, when a Vulkan API call emits a message, it is interrupted midway through its internal processing while the message is being processed. This means that the Vulkan API implementation may be in an inconsistent state (e.g. some thread-local mutex may be locked). If our message processing callback then proceeds to make another Vulkan API call, this new API call will observe that inconsistent implementation state, which can result in an arbitrarily bad outcome (e.g. a thread deadlock in the above example). Furthermore, the new Vulkan API call could later emit more messages, potentially resulting in infinite recursion. ↩

Context

In the previous chapter, we went through the process of loading the system’s Vulkan library, querying its properties, and setting up an API instance, from which you can query the set of “physical”1 Vulkan devices available on your system.

After choosing one or more2 of these devices, the next thing we will want to

do is set them up, so that we can start sending API commands to them. In this

chapter, we will show how this device setup is performed, then cover a bit of

extra infrastructure that you will also usually want in vulkano-based

programs, namely object allocators and pipeline caches.

Together, the resulting objects will form a minimal vulkano API context that

is quite general-purpose: it can easily be extracted into a common library,

shared between many apps, and later extended with additional tuning knobs if you

ever need more configurability.

Device selection

As you may have seen while going through the exercise at the end of the previous chapter, it is common for a system to expose multiple physical Vulkan devices.

We could aim for maximal system utilization and try to use all devices at the same time, but such multi-device computations are surprisingly hard to get right.3 In this introductory course, we will thus favor the simpler strategy of selecting and using a single Vulkan device.

This, however, begs the question of which device we should pick:

- We could just pick the first device that comes in Vulkan’s device list, which is effectively what OpenGL programs do. But the device list is ordered arbitrarily, so we may face issues like using a slow integrated GPU on “hybrid graphics” laptops that have a fast dedicated GPU available.

- We could ask the user which device should be used. But prompting that on every run would get annoying quickly. And making it a mandatory CLI argument would violate the basic UX principle that programs should do something sensible in their default configuration.

- We could try to pick a “best” device using some heuristics. But since this is an introductory course we don’t want to spend too much time on fine-tuning the associated logic, so we’ll go for a basic strategy that is likely to pick the wrong device on some systems.

To balance these pros and cons, we will use a mixture of strategies #2 and #3 above:

- Through an optional CLI argument, we will let users explicitly pick a device

in Vulkan’s device list using the numbering exposed by the

infoutility when they feel so inclined. - When this CLI argument is not specified, we will rank devices by device type (discrete GPU, integrated GPU, CPU emulation…) and pick a device of the type that we expect to be most performant. This is enough to resolve simple4 multi-device ambiguities, such as picking between a discrete and integrated GPU or between a GPU and an emulation thereof.

This device selection strategy makes can be easily implemented using Rust’s iterator methods. Notice that strings can be turned into errors for simple error handling.

use crate::Result;

use clap::Args;

use std::sync::Arc;

use vulkano::{

device::physical::{PhysicalDevice, PhysicalDeviceType},

instance::Instance,

};

/// CLI parameters that guide device selection

#[derive(Debug, Args)]

pub struct DeviceOptions {

/// Index of the Vulkan device that should be used

///

/// You can learn what each device index corresponds to using

/// the provided "info" program or the standard "vulkaninfo" utility.

#[arg(env, short, long)]

pub device_index: Option<usize>,

}

/// Pick a physical device

fn select_physical_device(

instance: &Arc<Instance>,

options: &DeviceOptions,

quiet: bool,

) -> Result<Arc<PhysicalDevice>> {

let mut devices = instance.enumerate_physical_devices()?;

if let Some(index) = options.device_index {

// If the user asked for a specific device, look it up

devices

.nth(index)

.inspect(|device| {

if !quiet {

eprintln!(

"Selected requested device {:?}",

device.properties().device_name

)

}

})

.ok_or_else(|| format!("There is no Vulkan device with index {index}").into())

} else {

// Otherwise, choose a device according to its device type

devices

.min_by_key(|dev| match dev.properties().device_type {

// Discrete GPUs are expected to be fastest

PhysicalDeviceType::DiscreteGpu => 0,

// Virtual GPUs are hopefully discrete GPUs exposed

// to a VM via PCIe passthrough, which is reasonably cheap

PhysicalDeviceType::VirtualGpu => 1,

// Integrated GPUs are usually much slower than discrete ones

PhysicalDeviceType::IntegratedGpu => 2,

// CPU emulation of GPUs is not known for being efficient...

PhysicalDeviceType::Cpu => 3,

// ...but it's better than other types we know nothing about

PhysicalDeviceType::Other => 4,

_ => 5,

})

.inspect(|device| {

if !quiet {

eprintln!("Auto-selected device {:?}", device.properties().device_name)

}

})

.ok_or_else(|| "No Vulkan device available".into())

}

}Notice the quiet boolean parameter, which suppresses console printouts about

the GPU device in use. This will come in handy when we will benchmark context

building at the end of the chapter.

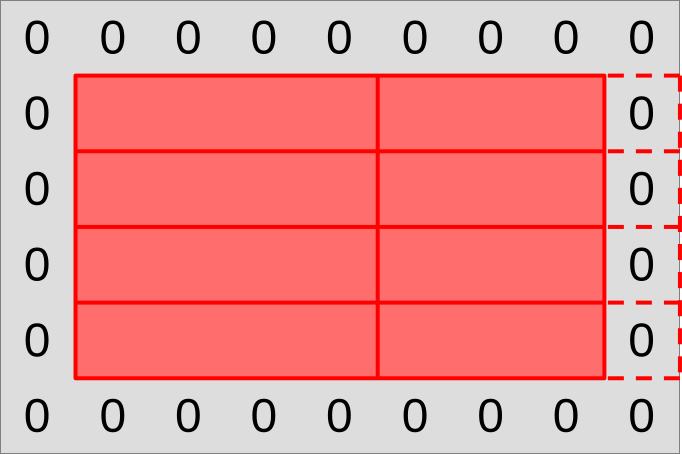

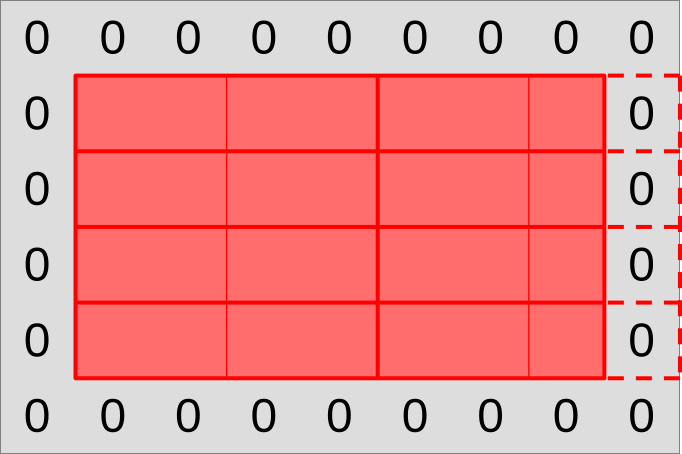

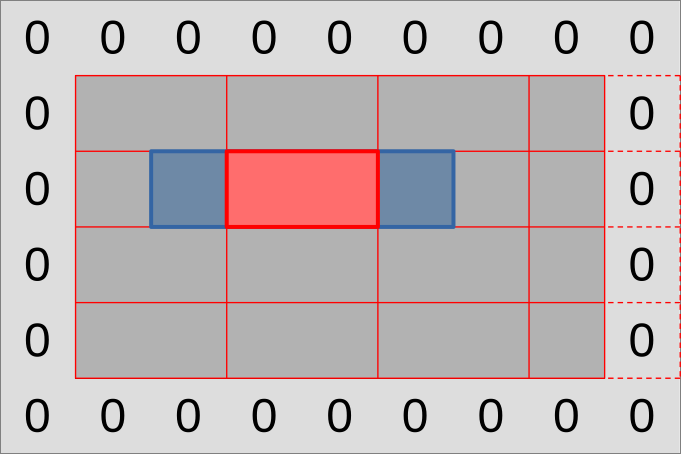

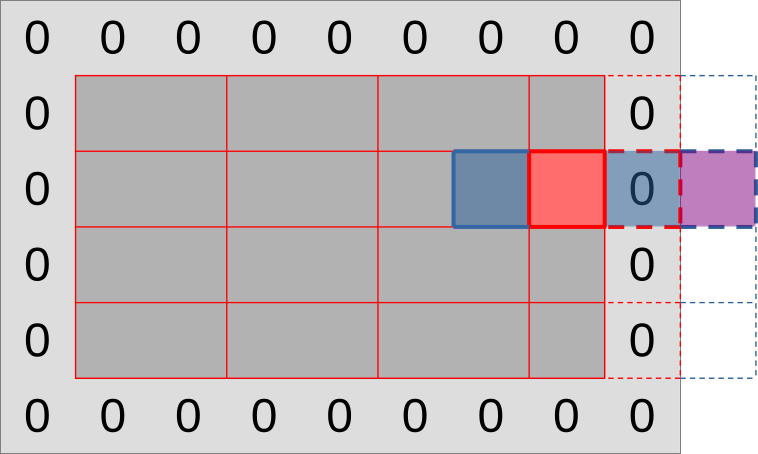

Device and queue setup