Async download

Introduction

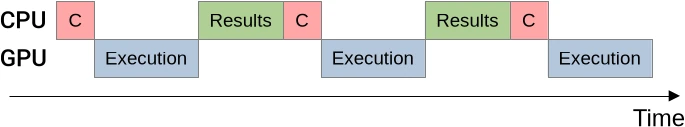

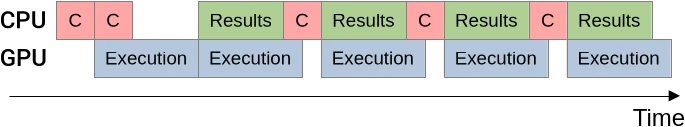

During the last chapter, we set up the required pipelining infrastructure for the CPU and GPU steps of computation to execute in parallel with each other. This took us from a situation where the CPU and GPU kept waiting for each other…

…to a situation where it is only the fastest device that awaits the slowest device:

However, the above diagrams are simplifications of a more complex hardware reality, where both the CPU and GPU work are composed of many independent components that can operate in parallel. By introducing more parallelism on either side, we should be able to improve our performance further. But how should we focus this effort?

On the CPU side, we mentioned multiple times that command buffer recording is relatively cheap. Which means we do not expect a massive performance benefit from offloading it to a different thread, and because of thread synchronization costs it could be a net loss. Beyond that, the other CPU tasks that we could consider parallelizing are all IO-related:

- NVMe storage and ramdisks like

/dev/shmare fast enough to benefit from the use of multiple I/O threads. But unfortunately the HDF5 library does not know how to correctly leverage multithreading for I/O, so we are stuck with our choice of file format here. - What we do control is the copy of GPU results from the main CPU thread to the I/O thread, which is currently performed in a sequential manner. But parallelizing memory-bound tasks like this is rather difficult, and we only expect significant benefits in I/O bound worloads that write to a ramdisk, which are arguably a bit of an edge case.

Taking all this into consideration, further CPU-side parallelization does not look very promising at this point. But what about GPU-side parallelization? That’s a deep topic, so in this chapter we will start with the first stage of GPU execution, which is the submission of commands from the CPU.

Right from this stage, a typical high-end modern GPU provides at least 2-3 flavors of independent hardware command submission interfaces, which get exposed as queue families in Vulkan:

- “Main” queues support all operations including traditional live 3D rendering.

- “Asynchronous compute” queues can execute compute commands and data transfer operations in parallel with the main queues when enough resources are available.

- Dedicated “DMA” queues, if available, can only execute data transfer commands but have a higher chance to be able to operate in parallel with the other queues.

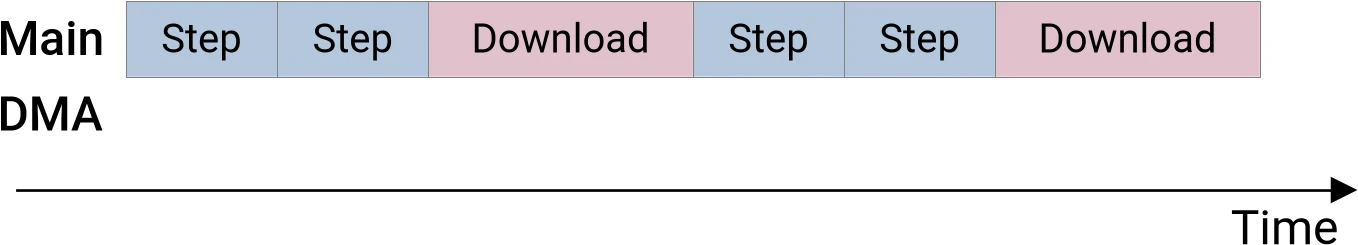

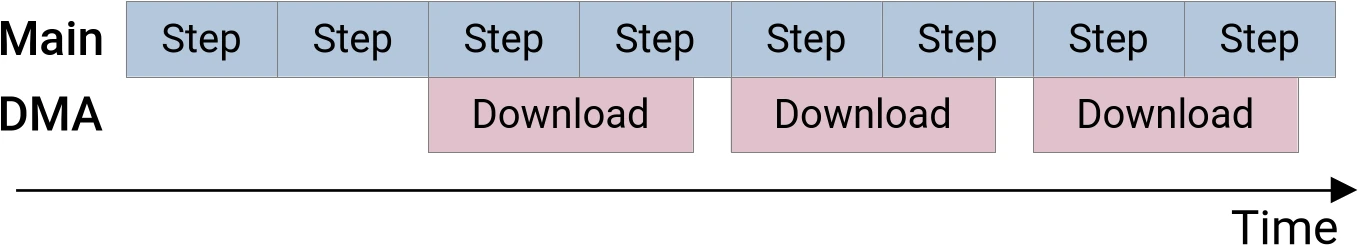

Knowing this, we would now like to leverage this extra hardware parallelism, if available, in order to go from our current sequential GPU execution model…

…to a state that leverages the hardware concurrent data transfer capabilities if available:

The purpose of this chapter will be to take us from here to there. From this optimization, we expect to improve the simulation’s performance by up to 2x in the best-case scenario where computation steps and GPU-to-CPU data transfers take roughly the same amount of time, and the application performance is limited by the speed at which the GPU does its work (as opposed to e.g. the speed at which data gets written to a storage device).

Transfer queue

To perform asynchronous data transfers, the first thing that we are going to

need is some access to the GPU’s dedicated DMA (if available) or asynchronous

compute queues.1 To get there, we will need to break an assumption that has

been hardcoded in our codebase for a while, namely that a single

Queue ought

to be enough for anybody.

The first step in this journey will be for us to rename our queue family selection function to highlight its compute-centric nature:

fn compute_queue_family_index(device: &PhysicalDevice) -> u32 {

device

.queue_family_properties()

.iter()

.position(|family| family.queue_flags.contains(QueueFlags::COMPUTE))

.expect("device does not support compute (or graphics)") as u32

}We will then write a second version of this function that attempts to pick up the device’s dedicated DMA queue (if available) or its asynchronous compute queue (otherwise). This is hard to do in a hardware-agnostic way, but one fairly reliable trick is to pick the queue family that supports data transfers and as few other Vulkan operations as possible:

/// Pick up the queue family that has the highest chance of supporting

/// asynchronous data transfers, and is distinct from the main compute queue

fn transfer_queue_family_index(device: &PhysicalDevice, compute_idx: u32) -> Option<u32> {

use QueueFlags as QF;

device

.queue_family_properties()

.iter()

.enumerate()

.filter(|(idx, family)| {

// Per the Vulkan specification, if a queue family supports graphics

// or compute, then it is guaranteed to support data transfers and

// does not need to advertise support for it. Why? Ask Khronos...

*idx != compute_idx as usize

&& family

.queue_flags

.intersects(QF::TRANSFER | QF::COMPUTE | QF::GRAPHICS)

})

.min_by_key(|(idx, family)| {

// Among the queue families that support data transfers, we priorize

// the queue families that...

//

// - Explicitly advertise support for data transfers

// - Advertise support for as few other operations as possible

// - Come as early in the queue family list as possible

let flags = family.queue_flags;

let flag_priority = if flags.contains(QF::TRANSFER) { 0 } else { 1 };

let specialization = flags.count();

(flag_priority, specialization, *idx)

})

.map(|(idx, _family)| idx as u32)

}We will then modify our device setup code to allocate one queue from each of these families…

/// Initialized `Device` with associated queues

struct DeviceAndQueues {

device: Arc<Device>,

compute_queue: Arc<Queue>,

transfer_queue: Option<Arc<Queue>>,

}

//

impl DeviceAndQueues {

/// Set up a device and associated queues

fn new(device: Arc<PhysicalDevice>) -> Result<Self> {

// Prepare to request queues

let mut queue_create_infos = Vec::new();

let queue_create_info = |queue_family_index| QueueCreateInfo {

queue_family_index,

..Default::default()

};

// Create a compute queue, and a transfer queue if distinct

let compute_family = compute_queue_family_index(&device);

queue_create_infos.push(queue_create_info(compute_family));

if let Some(transfer_family) = transfer_queue_family_index(&device, compute_family) {

queue_create_infos.push(queue_create_info(transfer_family))

}

// Set up the device and queues

let (device, mut queues) = Device::new(

device,

DeviceCreateInfo {

queue_create_infos,

..Default::default()

},

)?;

// Get the compute queue, and the transfer queue if available

let compute_queue = queues

.next()

.expect("we asked for a compute queue, we should get one");

let transfer_queue = queues.next();

Ok(Self {

device,

compute_queue,

transfer_queue,

})

}

}…and finally, we are going to integrate this new nuance into our context struct.

/// Basic Vulkan setup that all our example programs will share

pub struct Context {

pub device: Arc<Device>,

pub compute_queue: Arc<Queue>,

pub transfer_queue: Option<Arc<Queue>>,

pipeline_cache: PersistentPipelineCache,

pub mem_allocator: Arc<MemoryAllocator>,

pub desc_allocator: Arc<DescriptorSetAllocator>,

pub comm_allocator: Arc<CommandBufferAllocator>,

_messenger: Option<DebugUtilsMessenger>,

}

//

impl Context {

/// Set up a `Context`

pub fn new(

options: &ContextOptions,

quiet: bool,

progress: Option<ProgressBar>,

) -> Result<Self> {

let library = VulkanLibrary::new()?;

let mut logging_instance = LoggingInstance::new(library, &options.instance, progress)?;

let physical_device =

select_physical_device(&logging_instance.instance, &options.device, quiet)?;

let DeviceAndQueues {

device,

compute_queue,

transfer_queue,

} = DeviceAndQueues::new(physical_device)?;

let pipeline_cache = PersistentPipelineCache::new(device.clone())?;

let (mem_allocator, desc_allocator, comm_allocator) = setup_allocators(device.clone());

let _messenger = logging_instance.messenger.take();

Ok(Self {

device,

compute_queue,

transfer_queue,

pipeline_cache,

mem_allocator,

desc_allocator,

comm_allocator,

_messenger,

})

}

// [ ... same as before ... ]

}After this is done, we can let compiler errors guide us into replacing every

occurence of context.queue in our program with context.compute_queue. And

with that, we will get a program that still only uses a single Vulkan compute

queue… but now possibly allocates another data transfer queue that we will be

able to leverage next.

Triple buffering

Theory

Having reached the point where we do have access to a data transfer queue, we

could proceed to adjust our command buffer creation and queue submission logic

to perform asynchronous data transfers. But then we would once again get a

rustc or vulkano error, get puzzled by that error, think it through, and

after a while thank these tools for saving us from ourselves again.

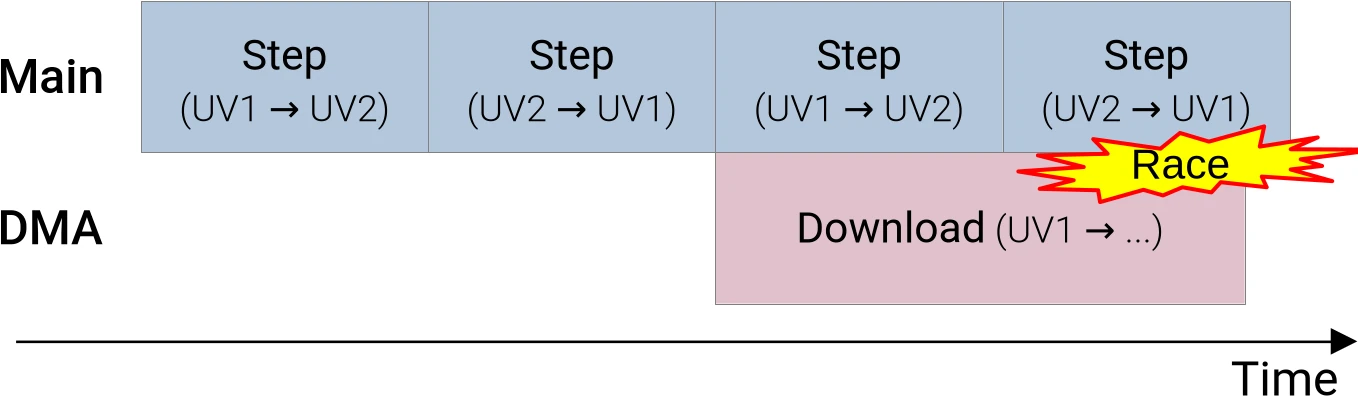

Indeed, asynchronous data transfers are yet another application on the general concept of pipelining optimizations. And like all pipelining optimizations, they require some kind of resource duplication in order to work. Without such duplication, we will once again face a data race:

In case the above diagram does not make it apparent, the problem with our

current memory management strategy is that if we try to download the UV1 version

of the V species’ concentration while running more simulation steps, and our

download takes more time than one simulation step, then subsequent simulation

steps will eventually end up overwriting the data that we are in the process of

transfering to the CPU, resulting in yet another data race.

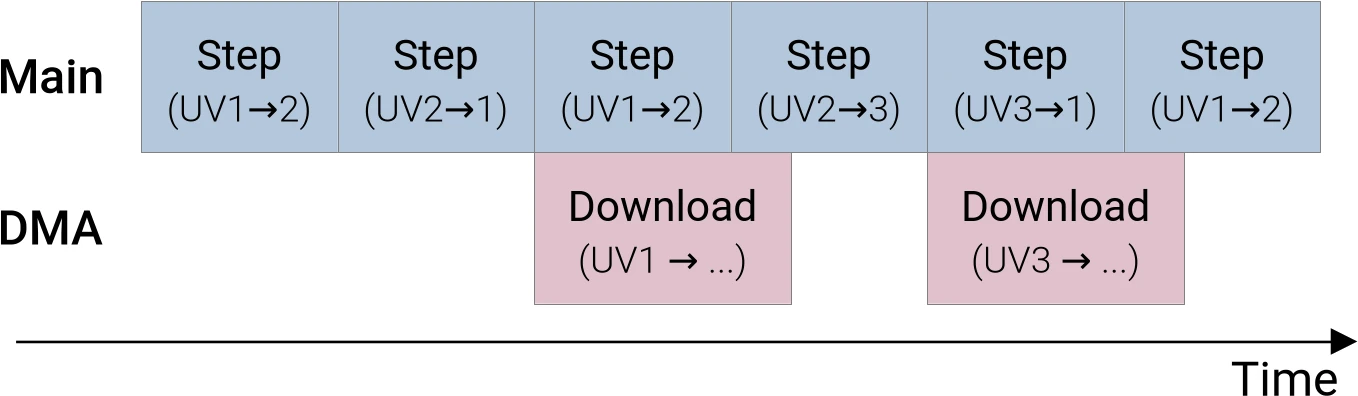

We can avoid this data race by allocating a third set of (U, V) concentrations

buffers on the GPU side. Which will allow us to have not just one, but three

pairs of (U, V) datasets, where each pair does not contain one of the three

(U, V) datasets…

- The

(UV2, UV3)pair does not containUV1 - The

(UV1, UV3)pair does not containUV2 - The

(UV1, UV2)pair does not containUV3

…and thus, by leveraging each of these pairs at the right time during our

simulation steps, we will be able to keep computing new simulation steps on the

GPU without overwriting the version of the (U, V) concentration data that is

in the process of being transferred to the CPU side:

But needless to say, getting there will require us to make “a few” changes to the logic that we use to manage our GPU-side concentration data storage. Which will be the topic of the next section.

Implementation

Previously, our Concentrations type was effectively a double buffer of

InOut, where each InOut contained a Vulkan descriptor set (for compute

pipeline execution purposes) and a V input buffer (for output downloading

purposes).

Now that we are doing triple buffering, however, we would need to have six such

InOut structs, with redundant V input buffers, and that starts to feel

wasteful. So instead of doing that, we will extract the descriptor set setup

logic out of InOut…

/// Set up a descriptor set that uses a particular `(U, V)` dataset as

/// inputs and another `(U, V)` dataset as outputs

fn setup_descriptor_set(

context: &Context,

layout: &PipelineLayout,

in_u: Subbuffer<[Float]>,

in_v: Subbuffer<[Float]>,

out_u: Subbuffer<[Float]>,

out_v: Subbuffer<[Float]>,

) -> Result<Arc<DescriptorSet>> {

// Determine how the descriptor set will bind to the compute pipeline

let set_layout = layout.set_layouts()[INOUT_SET as usize].clone();

// Configure what resources will attach to the various bindings

// that the descriptor set is composed of

let descriptor_writes = [

WriteDescriptorSet::buffer_array(IN, 0, [in_u, in_v]),

WriteDescriptorSet::buffer_array(OUT, 0, [out_u, out_v]),

];

// Set up the descriptor set according to the above configuration

let descriptor_set = DescriptorSet::new(

context.desc_allocator.clone(),

set_layout,

descriptor_writes,

[],

)?;

Ok(descriptor_set)

}…and trash the rest of InOut, replacing it with a new DoubleUV struct that

is just a double buffer of descriptor sets that does not even handle buffer

allocation duties anymore:

/// Double-buffered chemical species concentration storage

///

/// This manages Vulkan descriptor sets associated with a pair of `(U, V)`

/// chemical concentrations datasets, such that...

///

/// - At any point in time, one `(U, V)` dataset serves as inputs to the active

/// GPU compute pipeline, and another `(U, V)` dataset serves as outputs.

/// - A normal simulation update takes place by calling the

/// [`update()`](Self::update) method, which invokes a user-specified callback

/// with the descriptor set associated with the current input/output

/// configuration, then flips the role of the buffers (inputs become outputs

/// and vice versa).

/// - The [`current_descriptor_set()`](Self::current_descriptor_set) method can be used to query the

/// current descriptor set _without_ flipping the input/output roles. This is

/// useful for the triple buffering logic discussed below.

struct DoubleUV {

/// If we denote `(U1, V1)` the first `(U, V)` concentration dataset and

/// `(U2, V2)` the second concentration dataset...

///

/// - The first "forward" descriptor set uses `(U1, V1)` as its inputs and

/// `(U2, V2)` as its outputs.

/// - The second "reverse" descriptor set uses `(U2, V1)` as its inputs and

/// `(U2, V2)` as its outputs.

descriptor_sets: [Arc<DescriptorSet>; 2],

/// Truth that the "reverse" descriptor set is being used

reversed: bool,

}

//

impl DoubleUV {

/// Set up a `DoubleUV`

fn new(

context: &Context,

layout: &PipelineLayout,

u1: Subbuffer<[Float]>,

v1: Subbuffer<[Float]>,

u2: Subbuffer<[Float]>,

v2: Subbuffer<[Float]>,

) -> Result<Self> {

let forward = setup_descriptor_set(

context,

layout,

u1.clone(),

v1.clone(),

u2.clone(),

v2.clone(),

)?;

let reverse = setup_descriptor_set(context, layout, u2, v2, u1, v1)?;

Ok(Self {

descriptor_sets: [forward, reverse],

reversed: false,

})

}

/// Currently selected descriptor set

fn current_descriptor_set(&self) -> Arc<DescriptorSet> {

self.descriptor_sets[self.reversed as usize].clone()

}

/// Run a simulation step and flip the input/output roles

fn update(&mut self, step: impl FnOnce(Arc<DescriptorSet>) -> Result<()>) -> Result<()> {

step(self.current_descriptor_set())?;

self.reversed = !self.reversed;

Ok(())

}

}All the complexity of triple buffering will be handled by the top-level

Concentrations struct, which is the only one that has all the information

needed to take correct triple-buffering decisions. As the associated logic is

sophisticated, we will help maintenance with an fair amount of doc comments:

/// Triple-buffered chemical species concentration storage

///

/// This manages three `(U, V)` chemical concentration datasets in such a way

/// that the following properties are guaranteed:

///

/// - At any point in time, a normal simulation update can be performed using

/// the [`update()`] method. This method will...

/// 1. Invoke a user-specified callback with a descriptor set that goes from

/// one of the inner `(U, V)` datasets (let's call it `(Ui, Vi)`) to

/// another dataset (let's call it `(Uj, Vj)`).

/// 2. Update the `Concentrations` state in such a way that the next time

/// [`update()`] is called, the descriptor set that will be provided will

/// use the former output dataset (called `(Uj, Vj)` above) as its input,

/// and another dataset as its output (can either be the same `(Ui, Vi)`

/// dataset used as input above, or the third `(Uk, Vk)` dataset).

/// - At any point in time, the [`lock_current_v()`](Self::lock_current_v)

/// method can be called as a preparation for downloading the current V

/// species concentration. This method will...

/// 1. Return the [`Subbuffer`] associated with the current V species

/// concentration, i.e. the buffer that the next [`update()`] call will use

/// as its V concentration input.

/// 2. Update the `Concentrations` state in such a way that subsequent calls

/// to [`update()`] will not use this buffer as their V species

/// concentration output. The other two `(U, V)` datasets will be used in a

/// double-buffered fashion instead.

///

/// The underlying logic assumes that the user will wait for the current data

/// download to complete before calling `lock_current_v()` again.

///

/// [`update()`]: Self::update

pub struct Concentrations {

/// `Vi` buffer from each of the three `(Ui, Vi)` datasets that we manage.

v_buffers: [Subbuffer<[Float]>; 3],

/// Double buffers that leverage a pair of `(U, V)` datasets, such that the

/// double buffer at index `i` within this array **does not** use the `(Ui,

/// Vi)` dataset per the `v_buffers` indexing convention.

///

/// For example, the double buffer at index 1 does not use the `(U1, V1)`

/// dataset, it alternates between the `(U0, V0)` and `(U2, V2)` datasets.

double_buffers: [DoubleUV; 3],

/// Currently selected entry of `double_buffers`, used for `update()` calls

/// after any `transitional_set` has been taken care of.

double_buffer_idx: usize,

/// Descriptor set used to perform the transition between two entries of the

/// `double_buffers` array.

///

/// Most of the time, simulation updates are fully managed by one

/// [`DoubleUV`], i.e. they keep going from one `(Ui, Vi)` dataset to

/// another `(Uj, Vj)` dataset and back, while the third `(Uk, Vk)` dataset

/// is unused. However, when [`lock_current_v()`] gets called...

///

/// - If we denote `(Ui, Vi)` the dataset currently used as input, it must

/// not be modified as long as the download scheduled by

/// [`lock_current_v()`] is ongoing. Therefore, the next simulation

/// updates must be performed using another double buffer composed of the

/// other two `(Uj, Vj)` and `(Uk, Vk)` datasets.

/// - Before this can happen, we need to take one simulation step that uses

/// `(Ui, Vi)` as input and one of `(Uj, Vj)` or `(Uk, Vk)` as output, so

/// that one of these can become the next simulation input.

///

/// `transitional_set` is the descriptor set that is used to perform the

/// simulation step described above, before we can switch back to our

/// standard double buffering logic.

///

/// [`lock_current_v()`]: Self::lock_current_v

transitional_set: Option<Arc<DescriptorSet>>,

}The implementation of this new Concentrations struct starts with the buffer

allocation stage, which is largely unchanged compared to what

InOut::allocate_buffers() used to do. We simply allocate 6 buffers instead of

4, because now we need three U storage buffers and three V storage buffers:

impl Concentrations {

/// Allocate the set of buffers that we are going to use

fn allocate_buffers(

options: &RunnerOptions,

context: &Context,

) -> Result<[Subbuffer<[Float]>; 6]> {

use BufferUsage as BU;

let padded_rows = padded(options.num_rows);

let padded_cols = padded(options.num_cols);

let new_buffer = || {

Buffer::new_slice(

context.mem_allocator.clone(),

BufferCreateInfo {

usage: BU::STORAGE_BUFFER | BU::TRANSFER_DST | BU::TRANSFER_SRC,

..Default::default()

},

AllocationCreateInfo::default(),

(padded_rows * padded_cols) as DeviceSize,

)

};

Ok([

new_buffer()?,

new_buffer()?,

new_buffer()?,

new_buffer()?,

new_buffer()?,

new_buffer()?,

])

}

// [ ... ]

}The new version of the create_and_schedule_init() constructor will not be that

different from its predecessor at a conceptual level. But it will have a few

more buffers to initialize, and will also need to set the stage for triple

buffering shenanigans to come.

impl Concentrations {

// [ ... ]

/// Set up GPU data storage and schedule GPU buffer initialization

///

/// GPU buffers will only be initialized after the command buffer associated

/// with `cmdbuild` has been built and submitted for execution. Any work

/// that depends on their initial value must be scheduled afterwards.

pub fn create_and_schedule_init(

options: &RunnerOptions,

context: &Context,

pipelines: &Pipelines,

cmdbuild: &mut CommandBufferBuilder,

) -> Result<Self> {

// Allocate all GPU storage buffers used by the simulation

let [u0, v0, u1, v1, u2, v2] = Self::allocate_buffers(options, context)?;

// Keep around the three V concentration buffers from these datasets

let v_buffers = [v0.clone(), v1.clone(), v2.clone()];

// Set up three (U, V) double buffers such that the double buffer at

// index i uses the 4 buffers that do not include (Ui, Vi), and the

// "forward" direction of each double buffer goes from the dataset of

// lower index to the dataset of higher index.

let layout = &pipelines.layout;

let double_buffers = [

DoubleUV::new(

context,

layout,

u1.clone(),

v1.clone(),

u2.clone(),

v2.clone(),

)?,

DoubleUV::new(

context,

layout,

u0.clone(),

v0.clone(),

u2.clone(),

v2.clone(),

)?,

DoubleUV::new(context, layout, u0.clone(), v0.clone(), u1, v1)?,

];

// Schedule the initialization of the first simulation input

//

// - We will initially work with the double buffer at index 0, which is

// composed of datasets (U1, V1) and (U2, V2).

// - We will initially access it in order, which means that the (U1, V1)

// dataset will be the first simulation input.

// - Due to the above, to initialize this first simulation input, we

// need to bind a descriptor set that uses (U1, V1) as its output.

// - This is true of the reverse descriptor set within the first double

// buffer, in which (U2, V2) is the input and (U1, V1) is the output.

let double_buffer_idx = 0;

cmdbuild.bind_pipeline_compute(pipelines.init.clone())?;

cmdbuild.bind_descriptor_sets(

PipelineBindPoint::Compute,

pipelines.layout.clone(),

INOUT_SET,

double_buffers[double_buffer_idx].descriptor_sets[1].clone(),

)?;

let num_workgroups = |domain_size: usize, workgroup_size: NonZeroU32| {

padded(domain_size).div_ceil(workgroup_size.get() as usize) as u32

};

let padded_workgroups = [

num_workgroups(options.num_cols, options.pipeline.workgroup_cols),

num_workgroups(options.num_rows, options.pipeline.workgroup_rows),

1,

];

// SAFETY: GPU shader has been checked for absence of undefined behavior

// given a correct execution configuration, and this is one

unsafe {

cmdbuild.dispatch(padded_workgroups)?;

}

// Any dataset other than the (U1, V1) initial input must have its edges

// initialized to zeros.

//

// Only the edges need to be initialized. The values at the center of

// the dataset do not matter, as these buffers will serve as simulation

// outputs at least once (which will initialize their central values)

// before they serve as a simulation input.

//

// Here we initialize the entire buffer to zero, as the Vulkan

// implementation is likely to special-case this buffer-zeroing

// operation with a high-performance implementation.

cmdbuild.fill_buffer(u0.reinterpret(), 0)?;

cmdbuild.fill_buffer(v0.reinterpret(), 0)?;

cmdbuild.fill_buffer(u2.reinterpret(), 0)?;

cmdbuild.fill_buffer(v2.reinterpret(), 0)?;

// Once the command buffer is executed, everything will be ready

Ok(Self {

v_buffers,

double_buffers,

double_buffer_idx,

transitional_set: None,

})

}

// [ ... ]

}For reasons that will become clear later on, we will drop the idea of having a

current_inout() function. Instead, we will only have…

- An

update()method that is used when performing simulation steps, as before. - A new

lock_current_v()method that is used when scheduling a V concentration download.

We will describe the latter first, as its internal logic will motivate the

existence of the new transitional_set data member of the Concentrations

struct, which the update() method will later need to use in an appropriate

manner.

As mentioned above, lock_current_v() should be called after scheduling a set

of simulation steps, in order to lock the current (U, V) dataset for the

duration of the final GPU-to-CPU download. This will prevent the associated V

buffer from being used as a simulation output for the duration of the download,

and provide the associated Subbuffer to the caller so that it can initiate the

download:

impl Concentrations {

// [ ... ]

/// Lock the current V species concentrations for a GPU-to-CPU download

fn lock_current_v(&mut self) -> Subbuffer<[Float]> {

// [ ... ]

}

// [ ... ]

}The implementation of lock_current_v() starts with a special case which we

will not discuss yet, which handles the scenario where two GPU-to-CPU downloads

are initiated in quick succession without any simulation step inbetween. After

this, we get code for the general case where some simulation steps have occured

after the previous GPU-to-CPU download.

First of all, we use the index of the current double buffer and its reversed

flag in order to tell what are the index of the current input and output buffer,

using the indexing convention introduced by the

Concentrations::create_and_schedule_init() constructor:

// [ ... handle special case of two consecutive downloads ... ]

let initial_double_buffer_idx = self.double_buffer_idx;

let (mut initial_input_idx, mut initial_output_idx) = match initial_double_buffer_idx {

0 => (1, 2),

1 => (0, 2),

2 => (0, 1),

_ => unreachable!("there are only three double buffers"),

};

let initial_double_buffer = &self.double_buffers[initial_double_buffer_idx];

if initial_double_buffer.reversed {

std::mem::swap(&mut initial_input_idx, &mut initial_output_idx);

}From this, we trivially deduce which buffer within the

Concentrations::v_buffers array is our current V input buffer. We keep a copy

of it, that will be the return value of lock_current_v():

let input_v = self.v_buffers[initial_input_idx].clone();The remainder of lock_current_v()’s implementation will then be concerned

with ensuring that this V buffer is not used as a simulation output again as

long as a GPU-to-CPU download is in progress. The indexing convention of the

Concentrations::double_buffers array has been chosen such that this is just a

matter of switching to the double-buffer at index initial_input_idx…

let next_double_buffer_idx = initial_input_idx;…but before we start using this double buffer, we must first perform a

simulation step that takes the simulation input from our current input buffer

(which is not part of the new double buffer) to another buffer (which will be

part of the new double buffer since there are only three (U, V) pairs).

For example, assuming we are initially using the first double buffer (whose

members are datasets (U1, V1) and (U2, V2)) and our current input buffer is

(U1, V1), we will want to move to the second double buffer (whose members ars

datasets (U0, V0) and (U2, V2)) by performing one simulation step that goes

from (U1, V1) to (U0, V0) or (U2, V2).

It should be apparent that the active descriptor set within the current double

buffer (which, in the above example, performs a simulation step from dataset

(U1, V1) to dataset (U2, V2)) will always go to one of the datasets within

the new double buffer, so we can use it to perform the transition…

self.transitional_set = Some(initial_double_buffer.current_descriptor_set().clone());…but we must then configure the new double buffer’s reversed flag so that

the first simulation step that uses it goes in the right direction. In the above

example, after the transitional step that uses (U1, V1) as input and (U2, V2) as output, we want to the next simulation step to go from (U2, V2) to

(U0, V0), and not from (U0, V0) to (U2, V2).

This can be done by figuring out what will be the index of the input and output datasets in the first step that uses the new double buffer…

let next_input_idx = initial_output_idx;

let next_output_idx = match (next_double_buffer_idx, next_input_idx) {

(0, 1) => 2,

(0, 2) => 1,

(1, 0) => 2,

(1, 2) => 0,

(2, 0) => 1,

(2, 1) => 0,

_ => {

unreachable!(

"there are only three double buffers, each of which has \

one input and one output dataset whose indices differ from \

the double buffer's index"

)

}

};…and setting up the reversed flag of the new double buffer accordingly:

self.double_buffer_idx = next_double_buffer_idx;

self.double_buffers[next_double_buffer_idx].reversed = next_output_idx < next_input_idx;Once the Concentrations is set up in this way, we can return the input_v

that we previously recorded to the caller of lock_current_v(). And this is the

end of the implementation of the lock_current_v() function.

The update() method’s implementation is then written in such a way that any

transitional_step is taken first before using the current double buffer, to

make sure that any double buffer transition scheduled by lock_current_v()

is performed before the new double buffer is used…

impl Concentrations {

// [ ... ]

/// Run a simulation step

///

/// The `step` callback will be provided with the descriptor set that should

/// be used for the next simulation step. If you need to carry out multiple

/// simulation steps, you should call `update()` once per simulation step.

pub fn update(&mut self, step: impl FnOnce(Arc<DescriptorSet>) -> Result<()>) -> Result<()> {

if let Some(transitional_set) = self.transitional_set.take() {

// If we need to transition from a freshly locked (U, V) dataset to

// another double buffer, do so...

step(transitional_set)

} else {

// ...otherwise, keep using the current double buffer

self.double_buffers[self.double_buffer_idx].update(step)

}

}

}…and because this uses Option::take(), there is a guarantee that the

transitional simulation step will only be carried out once. After that,

Concentrations will resume using a simple double-buffering logic as it did before the current V buffer was locked.

There is just one edge case to take care of. If two GPU-to-CPU downloads are

started in quick succession, with not simulation step inbetween, then all the

buffer-locking work has already been carried out by the lock_current_v() call

that initiated the first GPU-to-CPU download.

As a result, we do not need to do anything to lock the current input buffer

(which has been done already), and can simply figure out the input_v buffer

associated with the current V concentration input and return it right away.

That’s what the edge case handling at the beginning of lock_current_v() does,

completing the implementation of this function:

impl Concentrations {

// [ ... ]

/// Lock the current V species concentrations for a GPU-to-CPU download

fn lock_current_v(&mut self) -> Subbuffer<[Float]> {

// If no update has been carried out since the last lock_current_v()

// call, then we do not need to change anything to the current

// Concentrations state, and can simply return the current V input

// buffer again. Said input buffer is easily identified as the one that

// future simulation updates will be avoiding.

if self.transitional_set.is_some() {

return self.v_buffers[self.double_buffer_idx].clone();

}

// Otherwise, determine the index of the input and output buffer of the

// currently selected descriptor set

let initial_double_buffer_idx = self.double_buffer_idx;

let (mut initial_input_idx, mut initial_output_idx) = match initial_double_buffer_idx {

0 => (1, 2),

1 => (0, 2),

2 => (0, 1),

_ => unreachable!("there are only three double buffers"),

};

let initial_double_buffer = &self.double_buffers[initial_double_buffer_idx];

if initial_double_buffer.reversed {

std::mem::swap(&mut initial_input_idx, &mut initial_output_idx);

}

// The initial simulation input is going to be downloaded...

let input_v = self.v_buffers[initial_input_idx].clone();

// ...and therefore we must refrain from using it as a simulation output

// in the future, which we do by switching to the double buffer that

// does not use this dataset (by definition of self.double_buffers)

let next_double_buffer_idx = initial_input_idx;

// To perform this transition correctly, we must first perform one

// simulation step that uses the current dataset as input and another

// dataset as output. The current descriptor set within the double

// buffer that we used before does take us from our initial (Ui, Vi)

// input dataset to another (Uj, Vj) output dataset, and is therefore

// appropriate for this purpose.

self.transitional_set = Some(initial_double_buffer.current_descriptor_set().clone());

// After this step, we will land into a (Uj, Vj) dataset that is part of

// our new double buffer, but we do not know if it is the first or the

// second dataset within this double buffer. And we need to know that in

// order to set the "reversed" flag of the double buffer correctly.

//

// We already know what is the index of the dataset that serves as a

// transitional output, and from that and the index of our new double

// buffer, we can tell what is the index of the third dataset, i.e. the

// other dataset within our new double buffer...

let next_input_idx = initial_output_idx;

let next_output_idx = match (next_double_buffer_idx, next_input_idx) {

(0, 1) => 2,

(0, 2) => 1,

(1, 0) => 2,

(1, 2) => 0,

(2, 0) => 1,

(2, 1) => 0,

_ => {

unreachable!(

"there are only three double buffers, each of which has \

one input and one output dataset whose indices differ from \

the double buffer's index"

)

}

};

// ...and given that, we can easily tell if the first step within our

// next double buffer, after the transitional step, will go in the

// forward or reverse direction.

self.double_buffer_idx = next_double_buffer_idx;

self.double_buffers[next_double_buffer_idx].reversed = next_output_idx < next_input_idx;

input_v

}

// [ ... ]

}VBuffers changes

To be able to use the new version of Concentrations, a couple of changes to

the VBuffers::schedule_download_and_flip() method are required:

- This method must now receive

&mut Concentrations, not just&Concentrations, as it now needs to modify theConcentrationstriple buffering configuration usinglock_current_v()instead of simply querying its current input buffer for the V concentration. - …and the output of

lock_current_v()tells it what the current V input buffer is, which is what it needs to initiate the GPU-to-CPU download.

Overall, the new implementation looks like this:

pub fn schedule_download_and_flip(

&mut self,

source: &mut Concentrations,

cmdbuild: &mut CommandBufferBuilder,

) -> Result<()> {

cmdbuild.copy_buffer(CopyBufferInfo::buffers(

source.lock_current_v(),

self.current_buffer().clone(),

))?;

self.current_is_1 = !self.current_is_1;

Ok(())

}Simulation runner changes

Now that our data management infrastructure is ready for concurrent computations and GPU-to-CPU downloads, the last part of the work is to update our top-level simulation scheduling logic so that it actually uses a dedicated data transfer queue (if available) to run simulation steps and GPU-to-CPU data transfers concurrently.

To do this, we must first generalize our command buffer builder constructor so that it can work with any queue, not just the compute queue.

fn command_buffer_builder(context: &Context, queue: &Queue) -> Result<CommandBufferBuilder> {

let cmdbuild = CommandBufferBuilder::primary(

context.comm_allocator.clone(),

queue.queue_family_index(),

CommandBufferUsage::OneTimeSubmit,

)?;

Ok(cmdbuild)

}Then we modify the definition of SimulationRunner to clarify that its internal

command buffer builder is destined to host compute queue operations only…

/// State of the simulation

struct SimulationRunner<'run_simulation, ProcessV> {

// [ ... members other than "cmdbuild" are unchanged ... ]

/// Next command buffer to be executed on the compute queue

compute_cmdbuild: CommandBufferBuilder,

}…which will lead to some mechanical renamings inside of the SimulationRunner

constructor:

impl<'run_simulation, ProcessV> SimulationRunner<'run_simulation, ProcessV>

where

ProcessV: FnMut(ArrayView2<Float>) -> Result<()>,

{

/// Set up the simulation

fn new(

options: &'run_simulation RunnerOptions,

context: &'run_simulation Context,

process_v: Option<ProcessV>,

) -> Result<Self> {

// Set up the compute pipelines

let pipelines = Pipelines::new(options, context)?;

// Set up the initial command buffer builder

let mut compute_cmdbuild = command_buffer_builder(context, &context.compute_queue)?;

// Set up chemical concentrations storage and schedule its initialization

let concentrations = Concentrations::create_and_schedule_init(

options,

context,

&pipelines,

&mut compute_cmdbuild,

)?;

// Set up the logic for post-processing V concentration, if enabled

let output_handler = if let Some(process_v) = process_v {

Some(OutputHandler {

v_buffers: VBuffers::new(options, context)?,

process_v,

})

} else {

None

};

// We're now ready to perform simulation steps

Ok(Self {

options,

context,

pipelines,

concentrations,

output_handler,

compute_cmdbuild,

})

}

// [ ... ]

}We then extract some of the code of the schedule_next_output() method into a

new submit_compute() utility method which is in charge of scheduling execution

of this command buffer builder on the compute queue…

impl<'run_simulation, ProcessV> SimulationRunner<'run_simulation, ProcessV>

where

ProcessV: FnMut(ArrayView2<Float>) -> Result<()>,

{

// [ ... ]

/// Submit the internal compute command buffer to the compute queue

fn submit_compute(&mut self) -> Result<CommandBufferExecFuture<impl GpuFuture + 'static>> {

// Extract the old command buffer builder, replacing it with a blank one

let old_cmdbuild = std::mem::replace(

&mut self.compute_cmdbuild,

command_buffer_builder(self.context, &self.context.compute_queue)?,

);

// Submit the resulting compute commands to the compute queue

let future = old_cmdbuild

.build()?

.execute(self.context.compute_queue.clone())?;

Ok(future)

}

// [ ... ]

}…and we use that to implement a new version of schedule_next_output() that

handles all possible configurations with minimal code duplication:

- User requested GPU-to-CPU downloads and…

- …a dedicated transfer queue is available.

- …data transfers should run on the same compute queue as other commands.

- No GPU-to-CPU downloads were requested, only simulation steps should be scheduled.

In terms of code, it looks like this:

impl<'run_simulation, ProcessV> SimulationRunner<'run_simulation, ProcessV>

where

ProcessV: FnMut(ArrayView2<Float>) -> Result<()>,

{

// [ ... ]

/// Submit a GPU job that will produce the next simulation output

fn schedule_next_output(&mut self) -> Result<FenceSignalFuture<impl GpuFuture + 'static>> {

// Schedule a number of simulation steps

schedule_simulation(

self.options,

&self.pipelines,

&mut self.concentrations,

&mut self.compute_cmdbuild,

)?;

// If the user requested that the output be downloaded...

let future = if let Some(handler) = &mut self.output_handler {

// ...then we must add the associated data transfer command to a

// command buffer, that will later be submitted to a queue

let mut schedule_transfer = |cmdbuild: &mut CommandBufferBuilder| {

handler

.v_buffers

.schedule_download_and_flip(&mut self.concentrations, cmdbuild)

};

// If we have access to a dedicated DMA queue...

if let Some(transfer_queue) = &self.context.transfer_queue {

// ...then build a dedicated data transfer command buffer.

let mut transfer_cmdbuild = command_buffer_builder(self.context, transfer_queue)?;

schedule_transfer(&mut transfer_cmdbuild)?;

let transfer_cmdbuf = transfer_cmdbuild.build()?;

// Schedule the compute commands to execute on the compute

// queue, then signal a semaphore, which will finally start the

// execution of the data transfer on the DMA queue

self.submit_compute()?

.then_signal_semaphore()

.then_execute(transfer_queue.clone(), transfer_cmdbuf)?

.boxed()

} else {

// If there is no dedicated DMA queue, make the data transfer

// execute on the compute queue after the simulation steps.

schedule_transfer(&mut self.compute_cmdbuild)?;

self.submit_compute()?.boxed()

}

} else {

// If there is no data transfer, then submit the compute commands

// to the compute queue without any extra.

self.submit_compute()?.boxed()

};

// Ask for a fence to be signaled once everything is done

Ok(future.then_signal_fence_and_flush()?)

}

// [ ... ]

}…and that’s it. No changes to SimulationRunner::process_output() and the

top-level run_simulation() entry points are necessary.

One thing worth pointing out above is the use of the

boxed()

adapter method from the GpuFuture trait of vulkano. This method will turn

our concrete GpuFuture implementations (which are arbitrarily complex

type-level expressions) into a single dynamically dispatched and heap-allocated

Box<dyn GpuFuture> type, so that all branches of our complex conditional logic

return an object of a same type, which is required in a statically typed

programming language like Rust.

If the compiler does not manage to optimize this out, it will result in some slight runtime overhead along the lines of those experienced when using of class-based polymorphism in object-oriented languages like C++ and Java. But by the usual argument that these overheads should be rather small compared to those of calling a complex GPU API like Vulkan, we will ignore these potential overheads for now, until profiling of our CPU usage eventually tells us to do otherwise.

Exercise

Implement the above changes in your Gray-Scott simulation implementation, and benchmark the effect on performance.

You should expect a mixed bag of performance improvements and regressions, depending on which hardware you are running on (availability/performance of dedicated DMA queues) and how much your simulation configuration is bottlenecked by GPU-to-CPU data transfers.

-

It should be noted that by allowing tasks on a command queue to overlap, the Vulkan specification technically allows implementations to perform this optimization automatically. But at the time of writing, in the author’s experience, popular Vulkan implementations do not reliably perform this optimization. So we still need to give the hardware some manual pipelining help in order to get portable performance across all Vulkan-supported systems. ↩